The Big Idea

Sell America in April, buy America in May

Steven Abrahams | July 25, 2025

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

After selling America in April, foreign debt investors decided to buy America in May. Foreign portfolios sold $32 billion in long US debt at the height of the tariff storm and then bought $204 billion the next month. The turnaround suggests it could be hard for foreign investors to quit US debt markets for now, putting limits on the speed and magnitude of further increases in US term premiums.

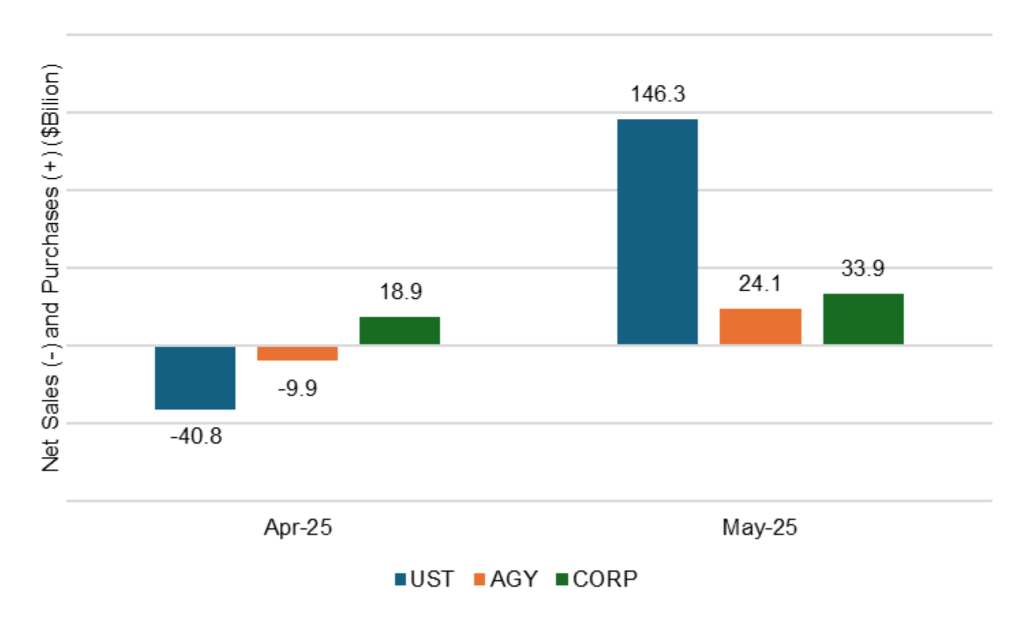

The turnaround came most clearly in Treasury and agency paper, based on the latest numbers from the Treasury International Capital system. Foreign investors sold $41 billion in US Treasury notes and bonds in April and then bought $146 in May (Exhibit 1). In agency debt and MBS, foreign portfolios sold $10 billion in April and bought $24 billion in May. Only in corporate and structured credit did foreign portfolios add in both months, buying $19 billion in April and another $34 billion in May.

Exhibit 1: Foreign flip-flop: $32 billion of April sells to $204 billion of May buys

Note: Data shows foreign net sales and purchases of securities with original term to maturity of more than 1 year.

Source: Monthly Holdings of US Long-Term Securities by Foreign Residents, Treasury International Capital System

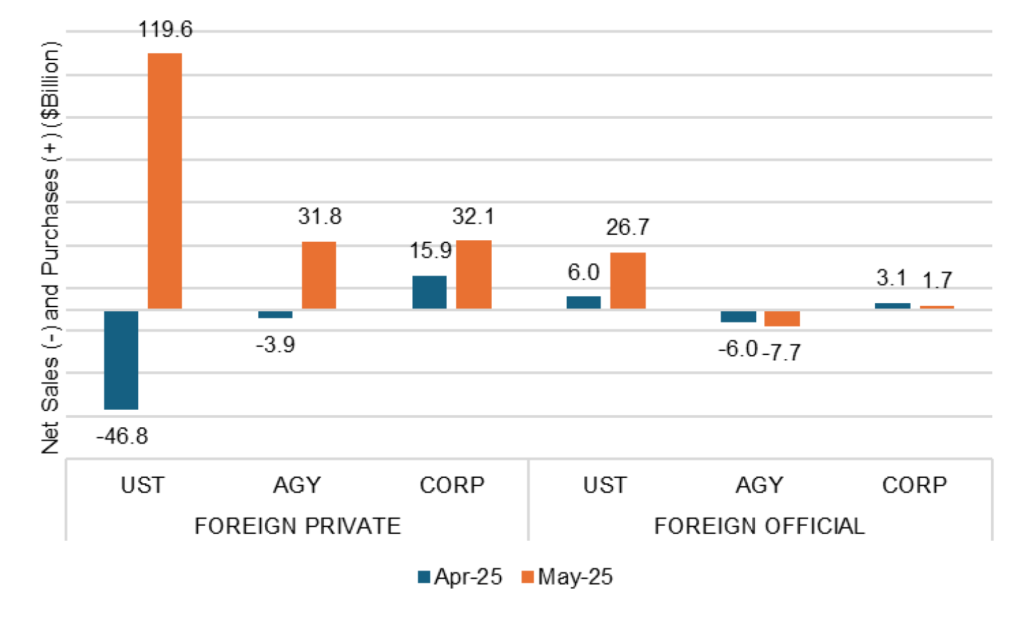

The turnaround came almost entirely from foreign private portfolios. Foreign banks, insurers, hedge funds and others collectively sold $47 billion in Treasury debt in April and then bought $120 billion in May (Exhibit 2). Those same portfolios also sold $4 billion in agency debt and MBS in April and bought $32 billion in May. And buying in corporate and structured credit went from $16 billion in April to $32 billion in May. Meanwhile, foreign central banks and other official government portfolios only modestly raised purchases of Treasury debt from April to May.

Exhibit 2: Foreign private portfolios led the flip-flop

Source: Monthly Holdings of US Long-Term Securities by Foreign Residents, Treasury International Capital System

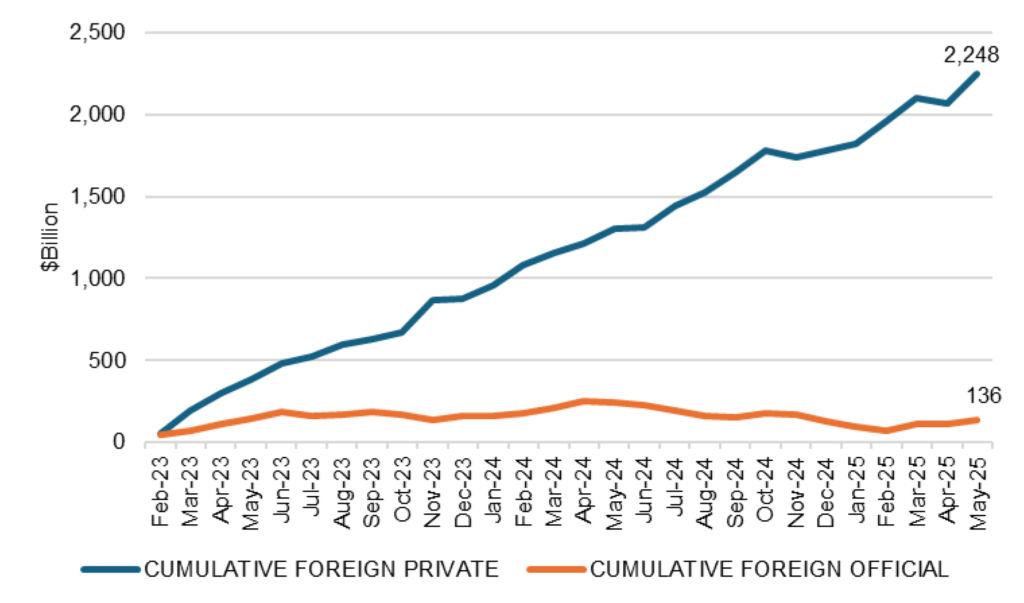

The strong hand of foreign private portfolios just continues a trend in place since the Global Financial Crisis, despite foreign central banks and other government portfolios leading the charge into US debt markets for a decade before then. Since the Treasury began reporting monthly purchases separately from changes in portfolio market value in February 2023, for example, foreign private portfolios have piled up $2.2 trillion in net purchases compared to foreign official portfolios’ $136 billion.

Exhibit 3: Foreign private portfolios have dominated US debt purchases for years

Source: Monthly Holdings of US Long-Term Securities by Foreign Residents, Treasury International Capital System

The turnaround from April to May could have come, of course, on a change in foreign investors’ view of prospects for US debt. Liberation Day had given way on April 9 to a 90-day pause on tariffs, and the US and China met in Switzerland in May and agreed to de-escalate their trade confrontation. That month could have marked the beginning of a return to business as usual.

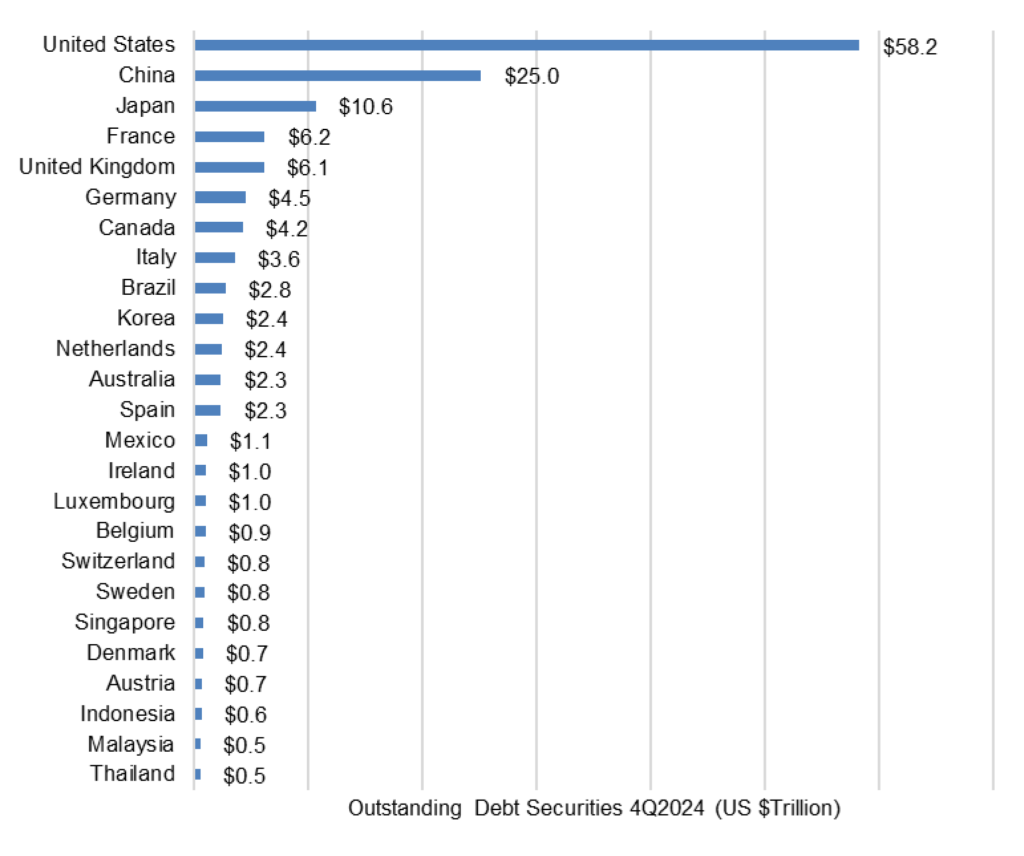

But the turnaround also could have come because foreign private portfolios have no other good alternative for now to the US debt securities markets. Most of these portfolios are in the business of investing against dollar liabilities or are benchmarked against a US dollar index and need dollar assets. At more than $58 trillion at the end of 2024, according to the Bank for International Settlements, the US markets offer a long menu of choices in liquidity, maturity, optionality, structure and exposure to government, corporate and household credits across a wide set of ratings (Exhibit 4). It may simply be too hard for private portfolios to find immediate alternatives in other markets that fit all their US dollar portfolio needs.

Exhibit 4: US debt markets offer depth and variety of debt exposures

Source: Bank for International Settlements Summary of Debt Securities Outstanding 4Q2024, Santander US Capital Markets

Even if foreign private portfolios have lingering concerns that led to selling in April, the business of investing and reinvesting current dollars may keep them coming back to US debt markets. That could keep foreign demand for US debt steady and slow any further widening in US term premiums.

That does not mean term premiums will necessarily fall. Concern among investors foreign and domestic about current and future US fiscal management likely explains a big part of the steady widening in term premium over the last few years and again this year. The US now has outstanding marketable Treasury debt equal to 100% of GDP and, according to the Congressional Budget Office, on the way to 124% or more. That raises questions about the ability of the current investor base to absorb supply in the long run. But beyond projected supply, there’s the issue of the market’s ability to absorb contingent supply—debt the US might have to issue to deal with recession, military conflict, pandemic or any other major pressing development. Swap spreads at longer maturities, a good proxy for term premiums, should be more sensitive to all of these risks. With more time, there’s more chance of unexpected demand on the budget.

The most likely base case for term premium: higher. It is hard to detect much political willingness in the US to either raise taxes or cut spending enough to make a difference. Of course, there are some ways term premiums could fall: US growth could surprise to the upside, Treasury could cut back on 10-year supply or the Fed could do another round of QE. None of those look likely. The trend for term premiums looks higher, but without any boost from selling America.

* * *

The view in rates

The market traded on Friday pricing fed funds at 3.87% to end the year, matching the Fed’s June dots exactly. The strong employment report for June has given the Fed some room to wait. And the Fed looks prepared to wait until it has a better view of whether tariffs will bring a 1-time price change or more persistent inflation. Presumably, any inflation impact from tariffs should start to play out in July and August. The market seems to believe the inflation impact will be muted or temporary or both with fed funds lower by the end of the year as a result.

A steady diet of tariff headlines has kept longer Treasury rates high relative to the swap curve. Add to that the steady pressure on the Fed and a debt-to-GDP ratio at 100% and expected to grow over the next decade to 124% after passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. It all promises to add term premium to the yield curve, steepening the curve.

Other key market levels:

- Fed RRP balances settled on Friday at $151 billion, down $48 billion on the week

- Setting on 3-month term SOFR closed Friday at 431 bp, down 1 bp in the last week.

- Further out the curve, the 2-year note traded Friday at 3.91%, up 4 bp in the last week. The 10-year note traded at 4.38%, down 4 bp in the last week.

- The Treasury yield curve traded Friday with 2s10s at 47 bp, flatter by 8 bp in the last week. The 5s30s traded Friday at 98 bp, flatter by 6 bp over the same period

- Breakeven 10-year inflation traded Friday at 242 bp, unchanged in the last week. The 10-year real rate finished the week at 196 bp, down 2 bp in the last week.

The view in spreads

Spreads look relatively tight against the Treasury curve. That seems to give a lot of weight to a benign outcome to the tariff standoff between the US and dozens of its trading partners. That helps risk assets continue to hold their ground against the Treasury curve. The Bloomberg US investment grade corporate bond index OAS traded on Friday at 77 bp, tighter by 1 bp in the last week. Nominal par 30-year MBS spreads to the blend of 5- and 10-year Treasury yields traded Friday at 148 bp, tighter by 1 bp in the last week. Par 30-year MBS TOAS closed Friday at 34 bp, unchanged in the last two weeks.

The view in credit

A wide range of specific industries and individual companies still have exposure to tariff risk, but fundamentals for the average of the distribution continue to look stable. Most investment grade corporate and most consumer balance sheets have fixed-rate funding so falling rates have limited immediate effect. Consumer debt service coverage is roughly at 2019 levels. However, serious delinquencies in FHA mortgages and in credit cards held by consumers with the lowest credit scores have been accelerating. Consumers in the lowest tier of income look vulnerable, and renewed student payments and cuts to government programs should keep the pressure on. The balance sheets of smaller companies show signs of rising leverage and lower operating margins. Leveraged loans also are showing signs of stress, with the combination of payment defaults and liability management exercises, or LMEs, often pursued instead of bankruptcy, back to 2020 post-Covid peaks. If the Fed only eases slowly this year, fewer leveraged companies will be able to outrun interest rates, and signs of stress should increase. LMEs are very opaque transactions, so a material increase could make important parts of the leveraged loan market hard to evaluate.