The Big Idea

Revisiting the Fed balance sheet

Stephen Stanley | October 17, 2025

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

Since the Fed began normalizing its balance sheet in 2022, Wall Street analysts have regularly predicted the Fed would be forced to end Quantitative Tightening within a few months. As I wrote several times in 2022 and 2023, these predictions were woefully off-base, as the Fed needed to shrink its balance sheet by trillions of dollars after massive expansion during the pandemic. After nearly three years, the Fed balance sheet is finally approaching the neighborhood of normal, and Chair Powell reignited talk of a quick end to QT in an October 14 speech. QT still looks on track to end sometime in the first half of next year.

Progress report

From the early days of QT, there were voices on Wall Street declaring that the Fed would soon end their balance sheet unwind. After these dramatic predictions repeatedly proved inaccurate, it created a “boy who cried wolf” mentality, perhaps lulling financial market participants to sleep. Chair Powell roused them in the last week, when he stated that “we may approach that point (to stop balance sheet runoff) in coming months.”

The Fed extended the timeframe of balance sheet normalization by twice over the past few years slowing the pace of Treasury runoff. The rationale was to minimize the likelihood that the Fed would grossly overshoot and create a shortfall in liquidity, as occurred in 2019. Since April, the Fed has been reducing its securities portfolio at a pace of roughly $20 billion per month ($5 billion in Treasuries plus whatever amount of MBS runoff occurs, usually around $15 billion per month).

As of early this month, the Fed’s securities portfolio had moved from a peak of $8.5 trillion in mid-2022 to $6.3 trillion, still nearly double the size prior to the pandemic (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Asset Side of the Fed Balance Sheet

Source: Federal Reserve.

One problem for the Federal Reserve is that, in the absence of outright selling, the ability to shed its MBS portfolio is limited by the pace of runoff. In over three years, the Fed has only been able to reduce its MBS holdings by around $600 billion. In fact, from the peak, the Fed’s Treasuries portfolio has fallen by $1.6 trillion, or over 2.5 times more than the MBS decline, even though the Fed is, in theory, aiming in the long-run for a Treasuries-only portfolio. More on this later.

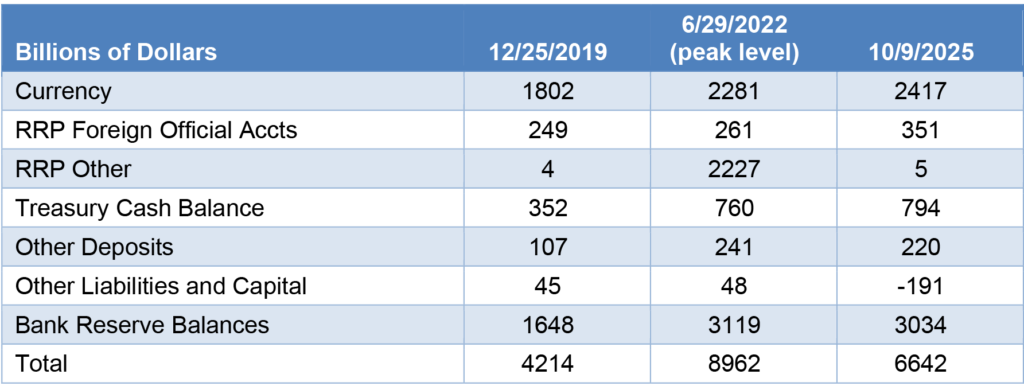

Meanwhile, the proper size of the balance sheet will be determined by the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet. Some of the major components are entirely out of the Fed’s control. For example, the Fed supplies currency at whatever level the public demands, and the Treasury cash balance is entirely up to government officials. The key variables on the liability side for the Fed are bank reserves, reverse RPs, “other deposits,” and “other liabilities and capital” (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Liability Side of the Fed Balance Sheet

Source: Federal Reserve.

A few observations. First, on balance, the entirety of the decline in liabilities since the peak, which totals $2.3 trillion, has been the drying up of the RRP program, which has gone from $2.23 trillion to virtually zero. Note that bank reserves have barely fallen since June 2022, remaining above $3 trillion, almost double the amount at the end of 2019.

While financial market participants and analysts have spilled gallons of ink speculating on the proper level of bank reserves, the Fed is trying to gauge the overall provision of liquidity. The metrics that Fed officials have indicated that they are monitoring include repo rates and other broader measures of money market liquidity. Thus, we can discuss a target level for bank reserves, but it is easy to conceive of the money market universe reaching balance at multiple levels of bank reserves, depending on the overall liquidity environment.

Another observation is that the demand for a significant portion of the Fed’s liabilities can vary according to the financial regulatory stance. Trump Administration officials have discussed the notion that the prevailing regulatory rules prior to 2025 were too stringent and that the safety and soundness of the system could be achieved with lower liquidity requirements. The new Fed Vice Chair for Supervision, Michelle Bowman, has signaled a similar stance. As a result, the “right” number for bank reserves may be lower a year from now than it was in the recent past, as banks’ demand for reserves would presumably decline in a more lenient regulatory environment. Similarly, the bulk of the “other deposits” line item reflects liquidity requirements that the Fed and financial regulators have imposed on key financial entities, such as central clearing outfits. The “proper” number for that variable could also decline if regulatory requirements ease.

The Fed offers a RRP facility for foreign official and international accounts. This is a nice service, but to the best of my knowledge, it is not a legal requirement. It is possible that at some point, the Fed could tweak the terms of this facility in a way that would encourage these institutions to invest their cash in the market rather than with the central bank.

The point is that the “right” levels for many of the key line items on the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet are not set in stone. They could fluctuate, and, indeed, they could fall noticeably over the next year or two if the regulatory stance relaxes.

In the end, the Fed is probably guessing along with everyone else about what the “right” size of the balance sheet is, but, as Chair Powell has noted many times, the Fed will monitor the situation and adapt as market conditions evolve. So, it is interesting to speculate about what the “right” size of the balance sheet is, but in the end, it is futile to try to offer any degree of precision on these projections.

As an aside, this logic also applies to the critique by Kevin Warsh and others that the Fed should shrink its balance sheet dramatically. Warsh’s case that the Fed does not need such a large balance sheet to effectively conduct monetary policy may be valid. Nevertheless, since the Fed seeks to calibrate the size of the balance sheet to meet the demand for liquidity in the financial system (plus the items beyond its control, like currency and Treasury’s cash balance), to get the balance sheet size down to wchere Warsh would apparently like to see it, which is much closer to where it was prior to the Global Financial Crisis, would probably require a dramatic change in the financial regulatory requirements for bank reserves. If Warsh (or someone sympathetic to his argument) is chosen as the next Fed chair, I will be very interested to hear more about how he would manage a large further reduction in the balance sheet.

The final observation is the dirty little secret that I discussed going back a couple of years but still may not be widely understood. The Fed is losing money in a major way, as the interest that it pays on bank reserves and RRP exceeds the returns that it earns on its securities portfolio. The “other liabilities and capital” line item reflects this. As the earlier columns of Exhibit 2 show, the normal state of affairs would be that the Fed holds close to $50 billion in capital. Thus, the current level of -$191 billion suggests that the Fed is almost $250 billion in the hole. The good news is that as the Fed lowers its policy rate, its losses will narrow. The red ink has only grown by about $25 billion in the first nine months of 2025, and, with another ease or two, the Fed may get back close to break even.

How does the Fed fill that hole in its finances? In essence, it prints money (I am sure there are thousands of companies over time facing operating losses that would have loved to have had that option!). It does so by creating an IOU that it will ultimately “pay back” by not remitting its returns to Treasury, as it usually would, until the “debt” is repaid. In any case, the arithmetic of Exhibit 2 should make clear that when the Fed creates these IOUs, something else on the liability side has to go up to make the numbers balance out. Thus, these IOUs effectively represent added bank reserves. That is to say that if everything else was equal and the Fed had not piled up a cumulative loss of $250 billion, then the level of bank reserves would have been almost $250 billion lower. Note that this means when the Fed begins to repay its paper losses, it will be extinguishing bank reserves, presumably requiring the Fed to replace that liquidity.

The Fed’s ideal balance sheet

Fed officials have been quite clear about what they would like their balance sheet to look like once they have an opportunity to get there. On the asset side, the Fed has made two key declarations. First, policymakers would prefer a Treasuries-only portfolio. Of course, it will presumably take many years for the Fed’s $2 trillion MBS holdings to prepay or mature. To offer a sense, the Fed’s MBS holdings fell by about $150 billion over the first nine months of this year.

So, the first Fed goal is, for the foreseeable future, aspirational rather than achievable. The track record of the past 10 years (two rounds of QT) strongly indicates that the Fed is not inclined to sell MBS securities outright. So, the MBS portfolio will only shrink to the extent that paper prepays and matures.

The key takeaway here is that the Fed will continue to allow its MBS holdings to run off even after QT ends. At that point, I fully expect the Fed to sustain MBS runoff exactly as it is now and to replace those maturing securities by buying Treasuries in what those of us with gray hair will remember as “coupon passes” and “bill passes” (and younger readers can associate with the QE operations conducted in the early 2010s and during and just after the pandemic).

The bottom line is that once the Fed decides to stabilize the size of the balance sheet, it will probably need to buy about $15 billion per month in Treasuries. Furthermore, after a transition period, the Fed will need to grow the balance sheet to keep up with the liquidity needs of an expanding economy, at which time it will begin buying Treasuries at an even faster pace.

The second aspect of the balance sheet is less definitive, as various Fed officials have offered somewhat different views on the maturity structure of the Treasury portfolio, but the majority of policymakers who have weighed in have expressed support for skewing growth in the Treasury portfolio toward Treasury bills. Currently, the Fed holds a mere $200 billion in Treasury bills compared to $4 trillion of notes, bonds, and TIPS. I would look for the FOMC to choose to try slowly over time to evolve the structure of its Treasury portfolio to track closer to the universe of outstanding Treasury debt.

Guessing when QT ends

Circling back to where we started, when will QT end? This is purely guesswork, as it amounts to predicting when the Fed will decide that liquidity in the money markets has tightened to their satisfaction. This is why Chair Powell was so vague on Tuesday. Recall that he said “we may approach that point in coming months,” which offers tremendous wiggle room.

Some of the same folks who have been intermittently predicting an imminent halt to QT for three years immediately responded to Powell’s speech by declaring that QT would halt next month. I am dubious of that. Powell added that “some signs have begun to emerge that liquidity conditions are gradually tightening.” Again, this is far from a firm declaration. It strikes me as a warning that we are nearing the timeframe when the Fed will begin to seriously engage. Certainly, if a halt to QT were imminent, I would have expected to have heard about it from Dallas Fed President Logan, an expert on the balance sheet from her time at the New York Fed managing it, and perhaps others on the FOMC.

In any case, for the better part of a year, I have had a June 2026 end date penciled in. One could argue that Powell’s speech suggests that a halt to QT could come a little earlier. It would not surprise me if Powell would like to close the book on QT before he steps down as chair in May 2026 as a way of clearing the decks for his successor. In any case, I would certainly feel comfortable with a projection of QT ending some time in the first half of next year.