By the Numbers

FICO and GEO lead the way in discount prepays

Brian Landy, CFA | October 28, 2022

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

Mortgage rates above 7% have pushed prices for most MBS well below par, leaving investors hunting for faster prepayment speeds to boost returns. But extensive history to guide prepayment decisions for this kind of market is hard to come by. Evidence from the past six months nevertheless shows low-credit borrowers, condos and co-ops, and borrowers from states like Tennessee, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah have offered the biggest boost to discount prepayment speeds.

Historical prepayment data for discount environments has been limited since interest rates have trended lower since the early 1980s. When interest rates did increase, it was usually not long before rates fell again and sent the MBS market into another refinance wave. But the market does have increasing evidence from 2022.

The biggest speedup in discount prepayments has come from picking the right states. Tennessee prepaid 18% faster than average, for example, while New York prepaid 18% slower than average; that means Tennessee loans prepaid almost 40% faster than New York loans. Many states such as Tennessee, Colorado and Arizona posted speeds from 10% to 20% faster than the average state (Exhibit 1). The fast states typically have had stronger housing markets and more population growth as people migrated to those states—those two things often being linked. Northeastern states tended to have more outmigration, lowering housing demand. And places like New York have expensive mortgage taxes that also suppress housing turnover.

Exhibit 1: Different states have big differences in prepayment speeds.

Shows the 5 fastest and 5 slowest states after excluding small volume states.

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Amherst Pierpont Securities.

The exhibit shows the percent faster or slower a loan in each state prepaid compared to the average state, after controlling for other collateral characteristics like gross coupon, loan age, loan size, property type, servicer, and other attributes. Each of the following exhibits follows the same process—show the effect of one attribute while holding all the rest constant. Performance covers only out-of-the-money loans from April through September.

However, it can be a challenge to monetize geography and other turnover stories. Most specified pools were built to protect against fast prepayments, not slow turnover. Some stories—low loan balance, for example—offer both. But otherwise it is difficult to find pure geography stories outside of New York, Florida, Texas, and Puerto Rico. But the speed differences due to geography can be big enough that pools with a higher concentration of faster or slower states may prepay differently, and the market might not be pricing them to account for these differences.

In new issue, it might be possible to assemble a pool of fast turnover states that do not provide refinance protection for a nominal, or no, pay-up. This used to be more challenging because originators were able to sell more jumbo loans into TBA pools if they also included low pay-up loans. But agency jumbo production has slowed from a combination of higher loan limits, higher mortgage rates, and better jumbo execution in non-agency securitizations. So a lot of originators are operating below the de minimis limit and might be more willing to create low pay-up specified pools.

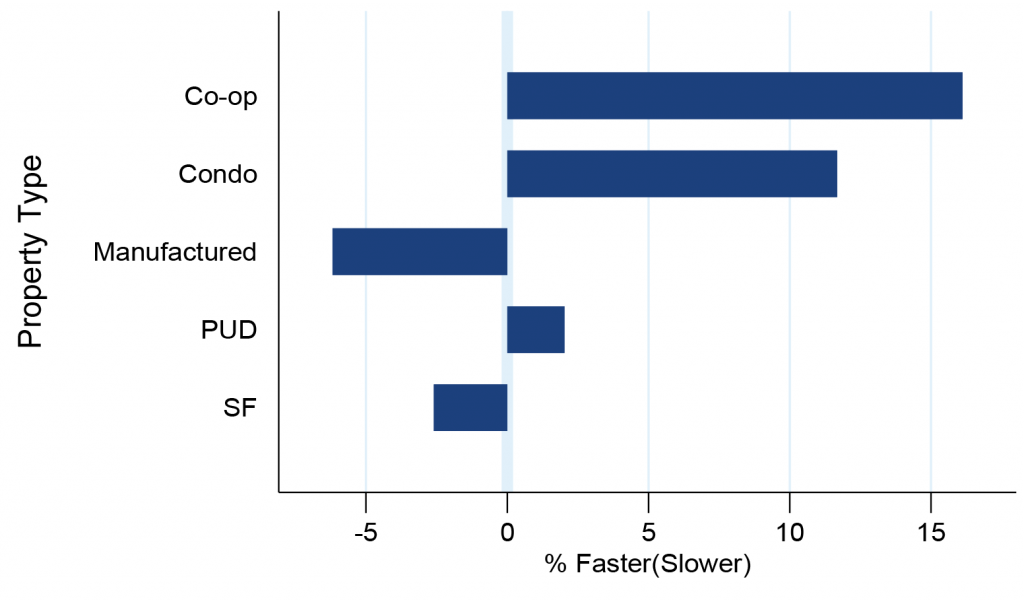

Condominiums and co-ops have been turning over faster than other property types (Exhibit 2). This could reflect that people who buy condos and co-ops are more likely to need a larger home in the future. There is also a small difference between planned urban developments and normal single-family homes. This might be a geographic difference at the MSA-level that can’t be controlled for since Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac only disclose each loan’s state. Manufactured housing has been prepaying slower than average.

Exhibit 2: Condos and co-ops tend to prepay faster than other loan types.

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Amherst Pierpont Securities.

Low-credit borrowers typically prepay faster in a discount environment (Exhibit 3). There is a steady progression from slower to faster as credit score declines. Low-credit borrowers tend to move more frequently, since they often experience income growth, credit curing, and growing families that need larger homes. They also are more likely to do a cash-out refinance even if that means forfeiting a low rate on their current loan. And default rates may also be higher. The swings can be large; for example, there is about a 10% speed difference between the 700–725 FICO bucket and the 775–800 FICO bucket.

Exhibit 3: Borrowers with low credit scores have been prepaying faster.

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Amherst Pierpont Securities.

A couple servicers that are known to prepay quickly in a refinance environment have maintained that status as the market shifted to a purchase environment (Exhibit 4). Quicken and loanDepot are well ahead of other servicers, which was also true of their discount pools during the pandemic. Both are known to have strong cash-out refinance businesses, which likely explains the difference. Bank servicers tend to be a little slower than average.

Exhibit 4: Quicken and loanDepot maintained faster speeds in a turnover environment.

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Amherst Pierpont Securities.

It has been known for a while that loans with smaller balances tend to turnover faster. These borrowers are typically younger and are more likely to need a larger home. The LLB (≤$85,000) bucket is exceptionally fast, although the amount of production in those sizes is dwindling, a result of fast home price appreciation over the last two years.

Exhibit 5: Smaller balance loans have faster housing turnover.

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Amherst Pierpont Securities.

A few other attributes had only small effects on turnover speeds. This included current LTV, presence of mortgage insurance, first time home buyers, and loan purpose.

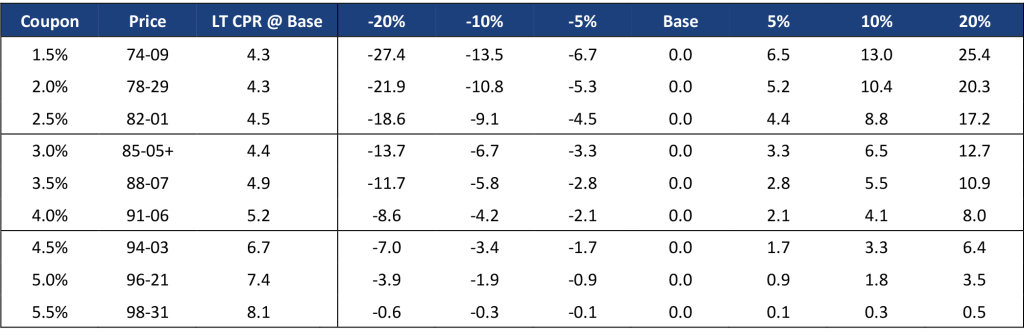

Small speed differences can have a large effect on value for pools priced below par (Exhibit 6). The table shows how much the price of each TBA increases or decreases if turnover is 5%, 10%, or 20% faster or slower than the base case speed shown. In the most extreme case—a 20% move in housing turnover for FNCL 1.5%s—the price can change by more than 25/32s.

Exhibit 6: Theoretical pay-up for scenarios of faster or slower housing turnover (32s)

Pay-up in 32\s using Yield Book’s production model for % faster/ or slower housing turnover over the model’s base-case projections.

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Yield Book, Amherst Pierpont Securities.