The Big Idea

Inflation, profit margins and credit

Steven Abrahams | September 16, 2022

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

As the Fed takes away the punchbowl, closes the bar and gives speeches about its willingness to turn out the lights, the profit party at US corporations is almost certainly about to end. Inflation and profitability tend to rise and fall together. And the market expects the Fed to win its inflation fight. That explains the dismal performance in equities and credit this year, especially with each new hawkish Fed speech or each new report pointing to persistent inflation. It also explains the continuing vulnerability of those markets.

Record profit margins

Businesses in the last few years have realized some of the highest absolute profits and widest profit margins in recent memory. Margins after tax as a share of nominal GDP rose through June to nearly 12%, the highest mark in more than three decades (Exhibit 1). After adjusting for gains in inventory and amortization, margins still touched 10.5%, also a generational high print. Rising profits have helped deleverage balance sheets and add liquidity, both credit positives. Life has been good for most shareholders and creditors.

Exhibit 1: Corporate profit margins have reached their highest mark in decades

Source: Federal Reserve, Amherst Pierpont Securities

Prices up faster than costs

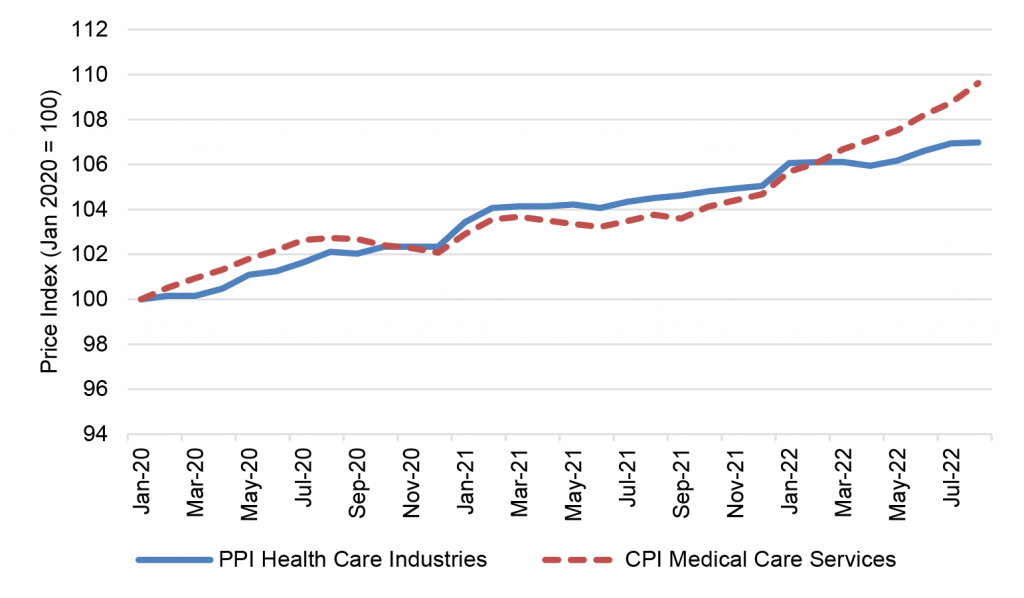

Widening margin have generally come not from cutting costs but from pushing up prices. It is hard to track markups, but not impossible. Manufacturers of new vehicles, for instance, have seen costs go up since the start of 2020 by 7.4%, but the price of a new vehicle has jumped 18.6% (Exhibit 2A). Healthcare costs and prices tracked each other closely until this year, and then prices pulled ahead (Exhibit 2B). Average retail margins also have gone up, according to the Fed.

Exhibit 2A: Vehicle prices have moved up much faster than manufacturing costs

Exhibit 2B: Prices for medical care services have outpaced health care costs

Source: Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

Fed Vice Chair Brainerd has argued that higher profit margins have contributed to inflation, but it is hard to draw the line between cause and effect. Margin could drive inflation, but general inflation could make consumers less sensitive to any particular price and encourage businesses to raise selected prices.

Margin and inflation trend together

Regardless of whether profit margins are cause or an effect of inflation, margin and inflation have often come together. Margins broadly rose with inflation from 2002 to 2008, fell with inflation in late 2008 and early 2009 before rebounding, trended sideways with inflation from 2010 through 2019 and have move higher together since. This shows up in the positive although noisy correlation between quarterly changes in profit margins and inflation (Exhibit 3). Work by the New York Fed also finds inflation helps lift corporate gross profits.

Exhibit 3: Margin and inflation tend to rise and fall together

Note: Quarterly data from 4Q1992 through 2Q2022.

Source: Federal Reserve, Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

The market expects a plunge in inflation

The market expects headline inflation to go into freefall from the current pace above 8% year-over-year. The 2-, 5- and 10-year breakeven inflation rates in the TIPS market all now range between 247 bp and 270 bp with the 5-year forward 5-year breakeven rate at 225 bp (Exhibit 4). To hit the 2-year breakeven of 253 bp, headline inflation will need to plunge from recent levels.

Exhibit 4: TIPS 2-year breakevens imply headline CPI will average 253 bp

Source: Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

It is not just the market. Consumers expect inflation to fall, too. Consumer expectations of inflation a year forward fell from 6.2% in July to 5.7% in August, according to the New York Fed’s latest Survey of Consumer Expectations. Expectations for inflation five years forward fell from 3.2% in July to 2.8% in August. Consumer inflation expectations in the University of Michigan survey also fell in August. Consumer expectations for inflation tend to be very sensitive to the price of gasoline and groceries, and declining fuel and food prices should continue bringing consumer inflation expectations down.

Lower inflation will be good for the Fed and should be good for the economy in the long run. In the short run, it should be bad for corporate profit margins and for equities and credit.

The challenge from persistent core inflation

The challenge for markets and credit will likely come from persistent core inflation, even if headline inflation falls. The Fed recognizes that wage inflation and rent have significant momentum and significant weights in core. Headline CPI from July to August rose only 0.1%, but core moved up 0.6%. Fed Governor Brainerd recently argued that financial conditions will become restrictive only when nominal fed funds stand 50 bp higher than contemporaneous expected inflation. In other words, terminal fed funds at 4%, for example, will only rein in inflation if expected core inflation is 3.5%–or increasing by 0.3% a month, half of last month’s pace. If core keeps rolling more than 0.3% each month, fed funds will have to go higher than the 4% mark that Fed Chair Powell and others have recently discussed. If the Fed begins to discuss higher terminal rates, expect equities to fall further and credit to widen.

* * *

The view in rates

The 2-year note closed Friday at 3.85%, up 29 bp from a week ago. It is comfortably in the range of fair value. The 10-year note closed well beyond fair value at 3.44%, up 13 bp on the week. The market now implies fed funds will peak around 4.30% early next year, consistent with a Fed more concerned about inflation than recession. Fair value at 10-year and longer maturities still looks anchored between 2.50% and 3.00%, the difference depending on expected persistence of inflation, and that should steadily draw 10-year yields lower. But the possibility of a sustained fight with inflation may require compensation above fair value even in long maturities. The 2s10s curve looks likely to invert by around 70 bp shortly before Fed tightening comes to an end.

Fed RRP balances closed Friday at $2.19 trillion, solidly in the range since mid-June. Yields on Treasury bills into early October continue to trade below the current 2.30% rate on RRP cash. Money market funds have little alternative but to put proceeds into RRP.

Settings on 3-month LIBOR have closed Friday at 353 bp, higher by 29 bp on the week. Setting on 3-month term SOFR closed Friday at 345bp, also higher by 29 bp.

Breakeven 10-year inflation finished the week at 238 bp, down 5 bp from a week before. The 10-year real rate finished the week at 106 bp, higher by 18 bp.

The Treasury yield curve has finished its most recent session with 2s10s at -41 bp, flatter by 16 bp on the week. The 5s30s finished the most recent session at -11 bp, flatter by 12 bp on the week.

The view in spreads

Volatility should continue while the Fed’s path stays in flux. Both MBS and credit have widened steadily since mid-August. Nominal par 30-year MBS spreads to the blend of 5- and 10-year Treasury yields finished the most recent session at 154 bp, wider by 10 bp on the week. Par 30-year MBS OAS finished the week at 40 bp, wider by 8 bp on the week. Investment grade cash credit spreads have finished the week unchanged at 164 bp over the SOFR curve.

The view in credit

Credit fundamentals have started to soften with the weakest credits showing slower revenue growth so far in 2022, declining free operating cash flow and less cash on the balance sheet. Ahead lays weaker demand, margin pressure, a soft housing market and various risks from Covid and supply interruptions. Inflation will land differently across different balance sheets. A recent New York Fed study argues inflation generally helps companies lift gross margins, although airlines and leisure may have an easier time passing through costs than healthcare, retail and restaurants. In leveraged loans, a higher real cost of funds would start to eat away at highly leveraged balance sheets with weak or volatile revenues. Consumer balance sheets look strong with rising income, substantial savings and big gains in real estate and investment portfolios. Homeowner equity jumped by $3.5 trillion in 2021, and mortgage delinquencies have dropped to a record low. But inflation and recession could take a toll and add credit risk to consumer balance sheets.