By the Numbers

A multifamily market shaped by lenders

Mary Beth Fisher, PhD | September 9, 2022

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

Not all parts of the multifamily market have equal prospects for growth ahead. Rapid growth in lending supported by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae along with lending by banks has meant steady growth for properties and borrowers that fit their respective underwriting. Prospects for healthy supply in that sector look good. For affordable housing, however, the supply of financing has retreated significantly. Supply in that sector looks likely to be highly constrained.

A decade of strong multifamily property price appreciation coincided with a shift in financing as the GSEs built market share in multifamily lending. The convergence of these trends has prompted some consolidation of multifamily holdings into the hands of institutional operators, primarily using lending channels of the GSEs and commercial banks. The dearth of very low-income housing is real, as direct federal or municipal government financing of public housing has plunged. The lending standards required of the GSEs and commercial banks, with only a trickle of public housing, will likely contribute to underbuilding in affordable housing and continued upward pressure on rent growth.

Multifamily mortgage financing has changed significantly since the late 1990s. Outstanding multifamily debt has risen from roughly $300 billion to approach nearly $2 trillion, with the share financed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae rising from 18% to 48% (Exhibit 1). Financing from commercial banks has dropped modestly from 37% to 30%. Financing by insurers has stayed roughly around 10%. Financing from federal, state and local governments has plunged from 21% to 6%. And financing from non-agency securitization has dropped from 16% in 2007 to less than 4% today.

Exhibit 1: Multifamily mortgages outstanding

Source: Federal Reserve, Amherst Pierpont Securities

With the GSEs and commercial banks providing nearly 80% of financing, their lending standards have important impact on the shape of multifamily properties and borrowers. The GSEs and banks both maintain lending standards subject to strict capital limits and regulatory controls. The GSEs, for example, naturally prefer multifamily owners and operators with substantial track records. This gives an edge to institutional operators, who then can accumulate large portfolios with the benefit of competitive financing. Smaller, private owners still tap the banks for financing, though they are competing with the deep pockets of private equity, and private equity can operate properties on thin initial cap rates while waiting for longer-term property price appreciation to earn larger returns.

The impact of lending standards is shaping the multifamily landscape slowly. There are approximately 19 million multifamily units with an estimated asset value of $5 trillion. Private, non-institutional investors still comprise the bulk of multifamily property owners, accounting for nearly two-thirds of multifamily assets by value (Exhibit 2). Institutional operators, or those that own large portfolios of properties, account for 10% of multifamily assets, while public REITs and private equity combine for 17%. Multifamily buildings that also serve as the primary residence for the owners are 12% of the stock.

Exhibit 2: Multifamily asset value by owner type

Note: Multifamily buildings are those with 5 or more units. Data as of Q2 2022.

Source: CoStar

The impact of lending standards is clearer in recent years. Multifamily transactions surged during the pandemic due to a combination of rent growth, property price appreciation and historically low costs of financing. This accelerated a marginal shift away from small, private multifamily operators towards institutional and private equity ownership (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Sales volume by buyer type over the past 12 months

Note: Data as of Q2 2022.

Source: CoStar

Institutional and private equity firms accounted for over a third of buyers, while private owners, public REITs and users were net sellers (Exhibit 4). Part of the very recent selling by REITs can be attributed to the compression on cap rates and higher cost of financing as the Fed raised interest rates in 2022.

Exhibit 4: Net multifamily buying and selling by owner type

Note: Data as of Q2 2022.

Source: CoStar

GSE and bank lending is likely to continue dominating multifamily finance, so the supply of properties that fit most easily into GSE and bank underwriting is likely to grow at the fastest pace. Demand is obviously is part of the equation driving rents, but supply in properties that fit the GSEs and banks should be less of a force for rent growth.

The double whammy for affordable housing

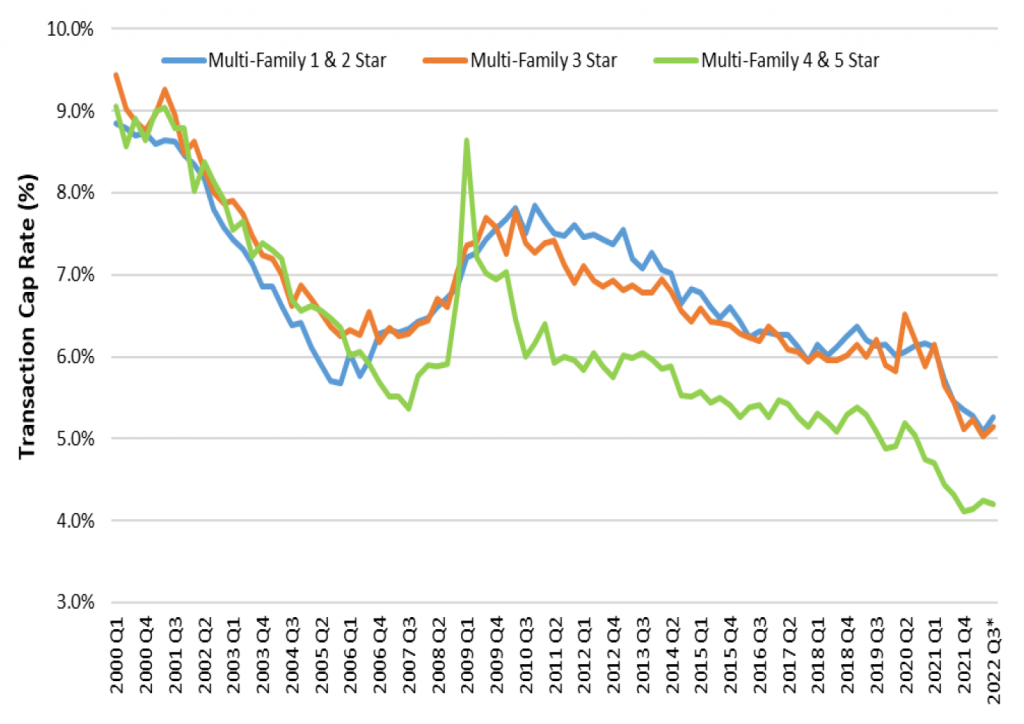

The attrition in spending for very low-income housing is evident in the decline of federal, state and local government multifamily assets, which now barely accounts for 6% of multifamily mortgage debt outstanding. Financing affordable to moderate income housing is also considered riskier since the housing crisis tightened lending standards for banks and the GSEs. Capitalization rates for multifamily 1- to 3-star buildings, which provide the bulk of affordable housing, are higher than those for 4- and 5-star buildings (Exhibit 5). These buildings do tend to be older and require more maintenance, the tenants can have lower credit scores, and tenant turnover can be higher. Building new moderate income housing in urban areas has also run up against zoning issues and faced pushback from community organizers, which has contributed to the lack of supply.

Exhibit 5: Multifamily capitalization rates by building class

Source: CoStar, Amherst Pierpont Securities

The GSEs make important contributions to affordable housing by asking developers to include affordable units. But if the finished building stabilizes and eventually sells without new GSE financing, the new owners can turn the affordable units into market rents. The affordable housing supply encouraged by GSE policy may not be permanent.

Private developers of affordable housing face significant costs in time and money to resolve zoning disputes and navigate neighborhood activism. Strict regulatory standards also reduce the incentive for commercial banks and the GSEs to lend to smaller borrowers, and for projects that are perceived to be riskier. All these factors contribute to a low- and middle-income housing supply shortage that is not being addressed. The downside for tenants is that the supply shortage looks unlikely to resolve anytime soon. Qualifying for affordable housing loans and other programs also often requires keeping rent to a fixed percentage of area median income, so there is a limit on rent growth. But the likely lack of supply implies little margin for rents to do anything but stay at their maximum allowable level.