The Big Idea

A surge in wages

Stephen Stanley | August 26, 2022

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

The extreme tightness of the labor market since the early days of pandemic has generated accumulating wage gains. For a time in the spring, a string of smaller monthly increases in average hourly earnings led some analysts to speculate that wage growth was decelerating. But that slowdown proved to be a false step, as the last two readings have been faster and have come with upward revisions to previous months. Perhaps more importantly, two alternative measures of wages that avoid the composition bias, the ECI and the Atlanta Fed wage tracker, are clearly accelerating.

Average hourly earnings

The most widely followed measure of wages is the average hourly earnings gauge released in the monthly employment report. There are actually two different average hourly earnings measures. The headline figure was introduced about 15 years ago and incorporates all workers. There is a narrower version that was the main reading until the newer, broader wage measure was rolled out. The narrower gauge includes only production and nonsupervisory workers—those who actually get paid by the hour.

Given that it is difficult to measure hourly pay for salaried workers or those who are paid on commission, there is a case to be made that the narrower version of average hourly earnings is more accurate, albeit less inclusive.

In any case, for a brief time in the spring, the two measures diverged somewhat, as the broader headline gauge slowed. The initial monthly prints for average hourly earnings beginning in February were flat, +0.4%, +0.3%, +0.3%, and +0.3%. If each of those preliminary readings had held, the annualized pace of wage gains over that five-month period would have been 3.2%, a steep moderation.

The initial readings have been revised mostly higher. Those same five readings, as they now stand, are +0.1%, +0.5%, +0.35%, +0.4%, and +0.4%, which works out to a 4.3% annualized pace. Moreover, the January readings was +0.6% and the July preliminary increase was +0.5%. The annualized pace for average hourly earnings over the first seven months of the year is 4.9%, which, as it happens is exactly the same as the 12-month rise in 2021.

Moreover, the narrower average hourly earnings measure has been rising faster than the broader version. So far this year, the monthly gains include one +0.3%, three 0.4%’s, and three 0.5%’s, working out to a 5.4% annualized pace.

All in all, the average hourly earnings data do not show the deceleration that they seemed to be pointing to a few months ago, but a case could be made that the numbers point to a steady trend for wage growth. If the story ended there, the Fed could probably live with that.

Alternative measures of worker compensation

The biggest problem with the average hourly earnings data is that they are subject to compositional bias. The gauge calculates the average wage of all of the workers that happen to be employed in a particular month, so the mix is always changing. We saw extreme examples of the potential bias during the pandemic. The bulk of the jobs that were lost early in the pandemic were in the bottom half of the pay scale, so the average wage shot up in the spring of 2020 and then sank in the summer, when the majority of those workers began to return.

Alternative measures of wages avoid that issue. The Employment Cost Index takes a quarterly snapshot of a fixed basket of job descriptions. For years, it barely moved, leading market participants to largely ignore the release. Starting last year, the ECI has begun to accelerate sharply.

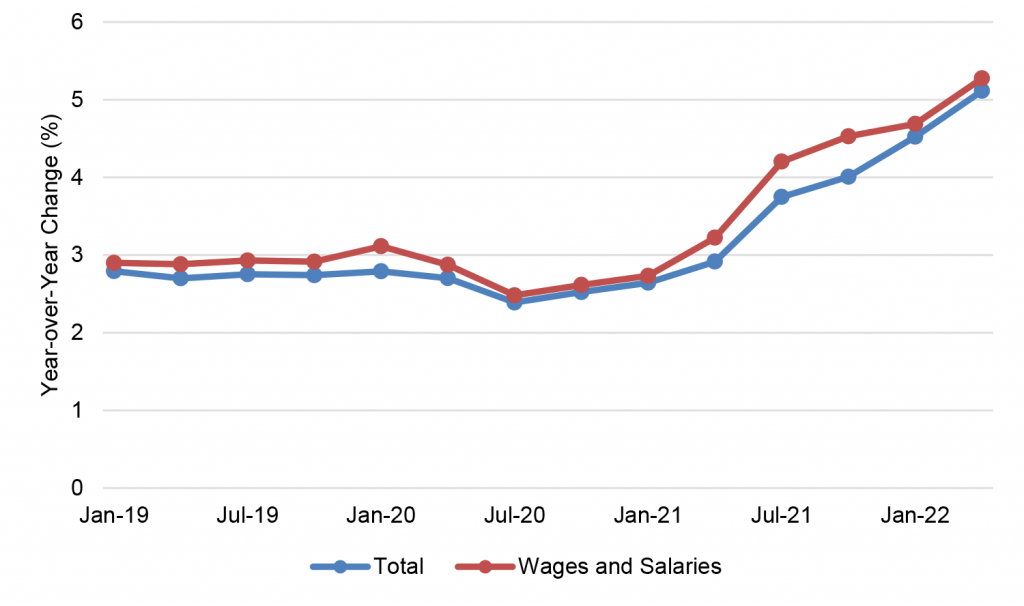

It helps to look at the quarterly changes in the headline ECI, which includes both wages and salaries and benefits, and the wage and salary component (Exhibit 1). The increases accelerated markedly last summer and have remained elevated through mid-2022.

Exhibit 1: ECI quarterly increases

Source: BLS.

Then look at the year-over-year advances for the headline ECI and the wage and salary component (Exhibit 2). Unlike the average hourly earnings figures, which surged much earlier in the pandemic but have been much closer to flat on a year-over-year basis over the last several quarters, the ECI points to an ongoing substantial acceleration in labor cost inflation.

Exhibit 2: ECI year-over-year growth

Source: BLS.

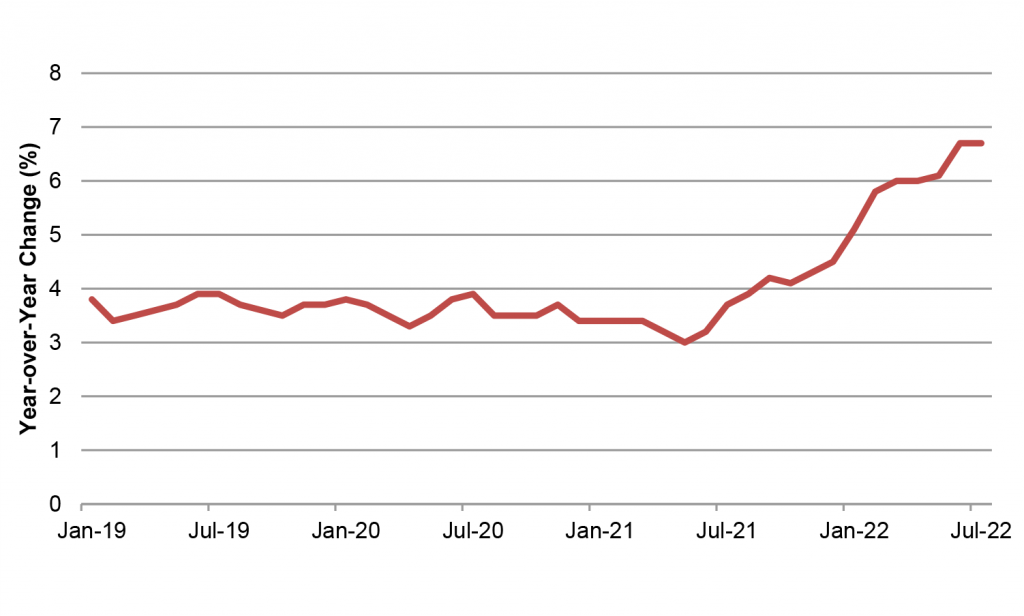

Another alternative wage measure that offers a unique perspective is the Atlanta Fed wage tracker. This gauge is derived from the Household Survey within the monthly Employment Report. This survey has a rotating panel, so not everyone participates every month. For a subset of the respondents, the Labor Department captures a wage reading for the latest month and a reading for the year-earlier month. As a result, like the Case-Shiller or FHFA home price index, this gauge allows a true apples-to-apples comparison. It measures the same person’s wages on a year-over-year basis. The downside is that the sample size is smaller than for the broader average hourly earnings measures.

Similar to the ECI, the Atlanta Fed wage tracker began to accelerate in earnest around the middle of last year and has been heating up since then (Exhibit 3). The gauge reached 6.7% in June and held there in July, exceeding the most recent corresponding readings for other wage indicators.

Exhibit 3: Atlanta Fed wage tracker year-over-year growth

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Looking at all of the wage data carefully, my conclusion is that pay gains are probably still accelerating. This should not be a particularly surprising finding, as the labor market remains extremely tight. While the demand for labor may be moderating at the margin, there is still a substantial imbalance between supply and demand in the labor market, which should, and appears to be, leading to accumulating wage pressures. It will be difficult for the Fed to bring underlying inflation down as long as the labor market is adding to upward price pressures.