The Big Idea

A consumer puzzle revisited

Stephen Stanley | June 10, 2022

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

The run-up in consumer credit earlier this year and the massive piles of unspent cash or equivalents sitting on household balance sheets seemed puzzling. Since then, another month’s consumer credit reading has rolling in and, more importantly, a quarterly update on household balance sheets. The updated data confirm that households are not tapped out but continue to possess vast stores of dry powder as we enter what is likely to be a robust summer for the consumer.

Consumer credit update

The Federal Reserve’s consumer credit data for April showed another noticeable rise in household borrowing. Overall consumer credit rose at a 10.1% annualized pace. However, that figure is not as impressive or alarming as it seems, especially considering that nominal consumer spending increased at an 11.4% annualized pace in the month. In particular, auto sales jumped in April, and the 7.1% annualized rise in nonrevolving debt likely is largely a reflection of more households buying or leasing new vehicles.

Meanwhile, revolving credit, mainly credit cards, posted a 19.6% annualized increase in April. However, as explained in a piece a few weeks ago, the run-up in credit card balances so far this year likely reflects sharply higher purchases, especially for big-ticket items like summer vacation bookings, rather than a sign of stress for the household sector in the aggregate. Keep in mind that if a household doubles the monthly charges on their credit cards in a given month but then pays off the balance in full, the consumer credit series will record roughly a doubling of debt—because it measures average daily balances—even though the household is not carrying debt in the sense that would cause macroeconomic concerns.

Moreover, revolving credit amounts to a relatively small item on household balance sheets. The consumer credit figures show that revolving credit barely exceeds $1 trillion, while nonrevolving credit accounts for close to three-quarters of consumer credit at nearly $3.5 trillion. Moreover, mortgage borrowing, which is not including in the consumer credit figures, is roughly $12 trillion. Meanwhile, household assets totaled $168 trillion in the first quarter, making credit card balances a mere drop in the bucket.

In any case, the level of revolving credit outstanding in April exceeded the 2019 average for the first time since the pandemic. That is, nominal credit card balances are roughly unchanged versus 2019, even as nominal income is up by 16.5% on a comparable basis. This is very far from a sign of stress for the household sector in the aggregate though it is undoubtedly the case that some individual households are likely struggling with excessive debt.

Household liquid assets still rising

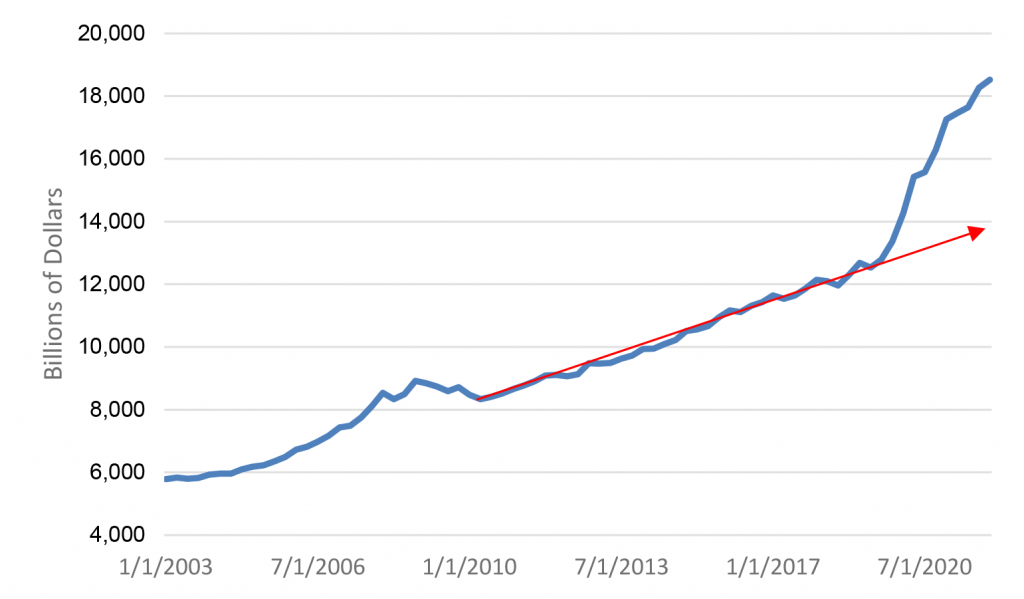

The updated data from the Federal Reserve’s quarterly Financial Accounts of the United States debunk the theory that households were spending down their accumulated savings in early 2022. It is true that household net worth fell slightly in the first quarter due to a drop in stock prices. However, household liquid assets continued to increase. The total of bank accounts and money market fund holdings rose by an additional $250 billion in the first quarter to $18.5 trillion (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Household Liquid Assets

Source: Federal Reserve.

The current level of household liquid assets is at least $4 trillion higher than the pre-pandemic trend line would suggest. That massive extra cushion should help to support consumer spending for years to come and will help to soften the blow to household purchasing power from the sharp acceleration in inflation.

To put the first quarter increase in perspective, the typical annual increase in this measure in the years prior to the pandemic was around $500 billion. Thus, the $250 billion rise in the first quarter indicates that consumers were amassing bank deposits and money market account balances about twice as fast as was the pre-pandemic norm. That is a far cry from the “consumers are burning through their savings” narrative espoused by some analysts.

I would qualify this analysis by noting that the aggregate tally of liquid assets is in nominal terms. I am often asked about how inflation is eating into consumers’ purchasing power. This is a valid concern. To offer some perspective on how inflation is impacting household savings, I would note that the liquid assets aggregate charted above increased at a 5.6% annualized pace in the first quarter while the PCE deflator rose at a 7.0% annualized clip. In real terms, household liquid assets did decline slightly in the first quarter of the year.

To offer an inflation-adjusted read, I deflated the liquid assets series by the PCE deflator (Exhibit 2). The broad conclusions hold. The amount of liquid assets has still risen sharply since the beginning of the pandemic, and the decline in the first quarter was trivial.

Exhibit 2: Real Household Liquid Assets

Source: Federal Reserve, BEA.