The Big Idea

Lessons learned in markets in 2021

Steven Abrahams | December 17, 2021

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

Markets can be excellent teachers, and so it was in 2021. Inflation came roaring back, but longer rates moved up only modestly. Credit fundamentals got stronger despite rising corporate expenses. Risk premiums stayed low. Taper started smoothly. And asset performance fell into a predictable pattern. None of these things might have seemed obvious at the start of the year, but they all offered important lessons.

#1: A clear and credible Fed is a powerful stabilizing force

The idea that annual inflation can run at 6.8% and US 10-year notes can trade at rates of 1.50% would have seemed almost unimaginable a year ago—and for most of Fed history—but here we are. Inflation last ran at 6.8% in March 1982, with 10-year yields near 14%. Something has changed, and that thing is the Fed’s careful cultivation of market expectations that it will pull out the stops to keep average inflation around 2%. Realized inflation had never tested Fed inflation targeting credibility as severely as it did in 2021, but the market suggests the Fed is passing with flying colors.

The TIPS market steadily priced expected 2-year inflation higher through 2021 as realized inflation continued to climb, but inflation at longer horizons, measured by 5-year forward 5-year expected inflation, generally stayed closer to the Fed’s 2% target (Exhibit 1). The stability of those expectations and the consequent stability of longer Treasury rates reflects at least two decades of effort by the Fed and other central banks to make policy transparent and credible. Those decades have seen the introduction of a broad set of tools—FOMC meeting statements, minutes, press conferences, economic and rate forecasts and speeches by members of the FOMC, among other things—that make policy and its objectives clear. In 1982, the market could only guess about what the Fed might do. Today, the Fed tells the market what it plans to do. And the market this year bought the Fed’s promise that inflation would eventually return to target.

Exhibit 1: Fed credibility likely kept long-term inflation expectations low in 2021

Source: Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

My colleague, Stephen Stanley, makes the fair point that the Fed cannot wait for inflation expectations to zoom higher before worry about inflation, but I would give a lot of weight to the Fed’s latest pivot to more aggressive tapering and its acknowledgement that inflation is not transitory. That sounds like a Fed willing to read the economic data and act, not a Fed waiting around complacently. It is also true that low inflation expectations cannot stop inflation in the short run. After all, oil price shocks come and go, fiscal spending rises and falls and, apparently, pandemics show up. But extensive experience in Canada, the UK, EU, Switzerland, Israel, Australia and Spain suggests that expectations are important for controlling inflation in the long run. The Fed’s efforts to manage expectations are important.

A relatively low level of expected inflation in the long run has made 10-year and longer rates relatively insensitive to inflation today. Actual inflation affects longer rates not like waves crashing on a beach but like ripples at the edge of a pond. As Stephen Stanley also points out that inflation has been naggingly difficult to model, and the Fed almost certainly will have to recalibrate policy next year as inflation keeps evolving. But the credibility of its commitment to low average inflation should make it very difficult for longer rates to build in anything much above 2% as an inflation risk premium.

#2 Credit loves inflation, at least over the short run and within limits

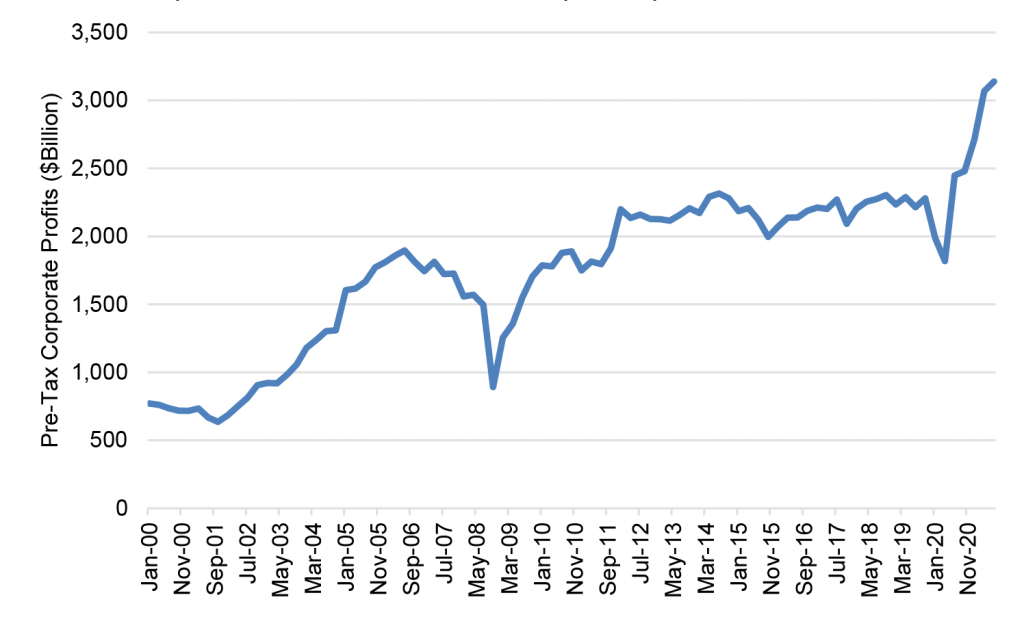

The idea that inflation can be good for corporate profits and for credit also would have invited some skepticism a year ago, but inflation has proven to be a corporate profit engine—or, at the very least, has not gummed up the works. Corporate profits and profit margins have surged to record levels in 2021, suggesting the revenue line of most corporate income statements is moving up faster than the expense line (Exhibit 2). The market seems to know this since a rise in TIPS inflation expectations typically comes with a tightening of credit spreads. Of course, that may not last if persistent high inflation sets the expense line in motion. We’re not there yet.

Exhibit 2: Despite or because of inflation, corporate profits have soared

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Amherst Pierpont Securities

My colleagues in investment grade corporate strategy, Meredith Contente and Dan Bruzzo, have noted recent management calls focused on pricing in a market with high inflation. Some companies are better than others. Extremely volatile inflation can wreck the ability of any company to generate profits. It becomes hard to set pricing if input costs can swing over short horizons. We’re not there yet, but that’s the basis of the Fed’s mantra that stable prices are essential to growth and full employment. For now, elevated inflation next year is likely to keep profits elevated, too.

#3: Markets can drown in liquidity

The ballooning of central bank balance sheets and the shift toward banking systems with high levels of liquid assets has almost surely helped stabilize the financial system and markets, but it has also drowned a lot of the sparks of market risk premium. One of the strongest influences on rates in 2021 was the increasing expectation that extraordinary excess liquidity would last for years, reflected in record low levels of real rates (Exhibit 3). Real rates in 2021 often went down faster than inflation expectations went up, driving down rates in the spring after rising inflation concerns pushed them up in February. The impact of all the cash in the system also shows up in today’s negative term premiums in US Treasury debt—a signal that investors stand to lose money by taking interest rate risk instead of rolling Treasury bills. It shows up, too, in tight spreads in agency MBS and credit.

Exhibit 3: Expected excess liquidity has driven US real rates to record lows

Source: Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

This lesson from 2021 suggests that any mispricings in the market are likely to be limited and short-lived, and that investors should expect risk-adjusted returns to run below historic averages. Portfolios that need to hit nominal income or return targets are likely to find themselves making investments they may not have considered before. The last year argues that this is the new normal.

#4: Taper does not always come with tantrum

The pandemic year of 2020 has to go down in the record books as one of the most dramatic Fed interventions in history, but 2021 may go down as one of the smoothest initial attempts at exit—initial, of course, because it will be a long, long time before the Fed winds down its intervention. In early 2021, with rates near zero, QE going full throttle and other Fed programs in place, it seems difficult to imagine the Fed even signaling taper without a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum. But by September, it was clear that the market showed almost no sign of concern—much less distress—at the prospect of tapering. Unlike 2013, 2- and 10-year rates remained stable, volatility barely budged and corporate spreads just moved sideways. MBS widened, but that arguably reflected Fed intentions to wind down QE.

The broader lesson may be that inflections in Fed policy do not have to destabilize markets. In the case of the current taper, the Fed could learn from its mistakes in 2013. It slowly heated up the conversation about tapering from January into November before making a formal announcement. By then, any market participant short of those operating on a desert island and communicating by corked bottle knew what was coming. The turn in policy was priced in. With enough lead time, the Fed can prepare the markets. As the Fed deals with inflation in the next year, it may not have the time it needs.

#5: Total return takes the other side of the Fed trade

Throughout 2021, credit—especially deep credit—turned in the best absolute and risk-adjusted investment performance. And the assets at the heart of QE, Treasury debt and MBS, often turned up among the worst. In fact, this pattern has repeated itself every quarter since the second quarter of 2020. Portfolios operating for total return either learned this lesson quickly or brought it along from Fed QE after 2008 because most sold Treasury debt and MBS steadily starting in the second quarter of 2020 and allocated into credit. The Fed squeezed opportunity out of its QE assets.

The lesson in asset returns from the last year argues the market should retire the trope “Don’t fight the Fed.” That sounds like good advice for a pre-QE world. In a post-QE world, the best advice might be “Cooperate with the Fed.” When the Fed wants to buy, then sell. Help the Fed with QE. And help yourself to better returns in other assets.

* * *

The view in rates

The Fed’s RRP facility is closing Friday with balances at a record balance of $1.704 trillion, up nearly $200 billion from a week ago. The supply of outstanding Treasury bills continues to shrink, and repo for general Treasury collateral is closing Friday at 3.3 bp. With the RRP facility paying 5 bp, it is getting record action.

Settings on 3-month LIBOR have closed Friday at 21.363 bp, up more than 0.5 bp in the last week and again hitting a local high. With the LIBOR-to-SOFR transition underway, it is worth noting that SOFR has not moved in months off it’s 5 bp mark, so the LIBOR-to-SOFR spread keeps widening. With a more aggressive taper, deceleration of liquidity and anticipated Fed hikes, yields even at the shortest end of the curve should start to rise.

The 10-year note has finished the most recent session at 1.40%, down 8 bp from a week ago. The December FOMC proved more hawkish than expected, The 10-year real rate finished the week at negative 103 bp, down 3 bp from a week ago. The market remains priced for significant excess liquidity in the future and an economy too slow to generate the borrowing needed to fully absorb it all.

The Treasury yield curve has finished its most recent session with 2s10s at 76 bp, flatter by 7 bp on the week, and 5s30s at 63 bp, unchanged on the week.

The view in spreads

The strands of pandemic, inflation, growth, labor and Fed policy create an unusually wide range of possible outcomes next year and beyond. Volatility should rise next year and add pressure for spreads to go wider, although tremendous market liquidity should push in the opposite direction.

Of the major spread markets, corporate and structured credit is likely to outperform. Corporates benefit from strong corporate fundamentals and buyers not tied to Fed policy. The biggest buyers of credit include money managers, international investors and insurers while the only net buyers of MBS during pandemic have been the Fed and banks. Credit buyers continue to have investment demand. Demand from Fed and banks should soften as taper begins, Once the Fed shows it hand on the timing and pace of taper, the market should be able to fully price the softening in Fed and bank demand and spreads should stabilize. But something else is on the horizon.

MBS stands to face a fundamental challenge in the next few months as the market starts to price the impact of higher Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loan limits. Home prices are tracking toward a nearly 20% year-over-year gain, which should get reflected in new agency loan limits traditionally announced in late November for loan delivered starting January 1. The jump in loans balances should add significant negative convexity to the TBA market and increase net supply. And this will come just as the Fed leans into tapering, which will take out a buyer that often absorbed the most negatively convex pools from TBA and a large share of net supply. The quality of TBA should deteriorate and the supply swell.

The view in credit

Credit fundamentals continue to look strong. Corporations have record earnings, good margins, low multiples of debt to gross profits, low debt service and good liquidity. The consumer balance sheet now shows some of the lowest debt service on record as a percentage of disposal income. That reflects both low rates and government support during pandemic. Rising home prices and rising stock prices have both added to consumer net worth, also now at a record although not equally distributed across households. Consumers are also liquid, with near record amounts of cash in the bank. Strong credit fundamentals may explain some of the relatively stable spreads.