The Big Idea

It’s all about liquidity, not inflation

Steven Abrahams | June 11, 2021

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

When the latest CPI printed up 5% from a year ago and core CPI printed up 3.8%, both above surveyed expectations, interest rates did not go up. Inflation expectations rose, at least based on 10-year breakeven rates. But the market’s view of the real cost of money over the next 10 years dropped that day sharply enough to drag 10-year nominal rates down by nearly 6 bp. Inflation surprise, but lower rates. Inflation is getting all the press, but the real story in rates is liquidity.

As my colleague Stephen Stanley illustrated so well earlier this month, the market has priced in an ample cushion for inflation, Potential for surprise is there, but it would have to be major to push the inflation component of rates off its mark. The CPI declined into May last year, so with this year’s May print the market has seen the strongest base effect on year-over-year CPI. The sprint to vaccinate most Americans and reopen the economy has led to a surge in demand that should eventually abate. On the labor front, for instance, more vaccinations, the opening of schools and the lapse of supplemental unemployment benefits should bring a supply of labor back into the work force sometime this fall. Supply should start to respond in other areas as well. The thing to watch is the path of year-over-year inflation, which should start to decelerate as soon as June. If year-over-year inflation does not slow down, that would likely be the surprise that would push rates higher.

Liquidity remains the bigger issue for the crowd routing for higher rates. One way for inflation to overshoot a single month’s expectations and trigger thoughts of liquidity would be for it to fail to overshoot enough to knock the Fed off its likely path. Global central bank QE, Fed preference for a banking system with high levels of excess reserves, foreign exchange reserves, demand for safe assets and even demographics stand to supply excess cash for years. One clear unknown is whether growth can eventually drive enough demand to borrow to soak up the expected cash and push up the real cost of money. With the consensus among economists looking for above-trend growth through 2022 before a glide back to the post-2008 average real GDP growth of 2%, the answer appears to be “no.” The market seems to agree.

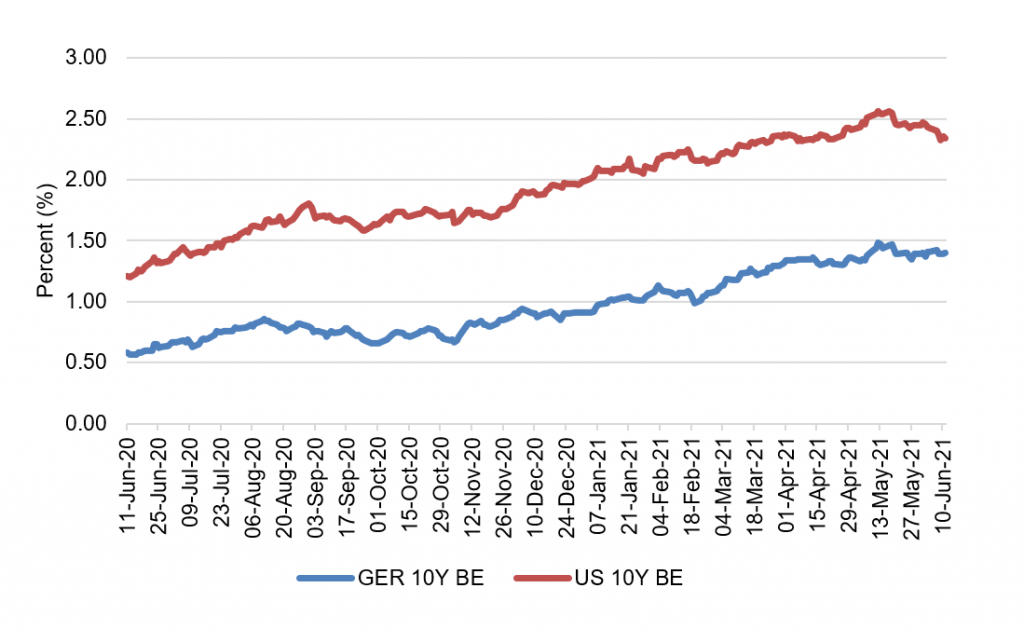

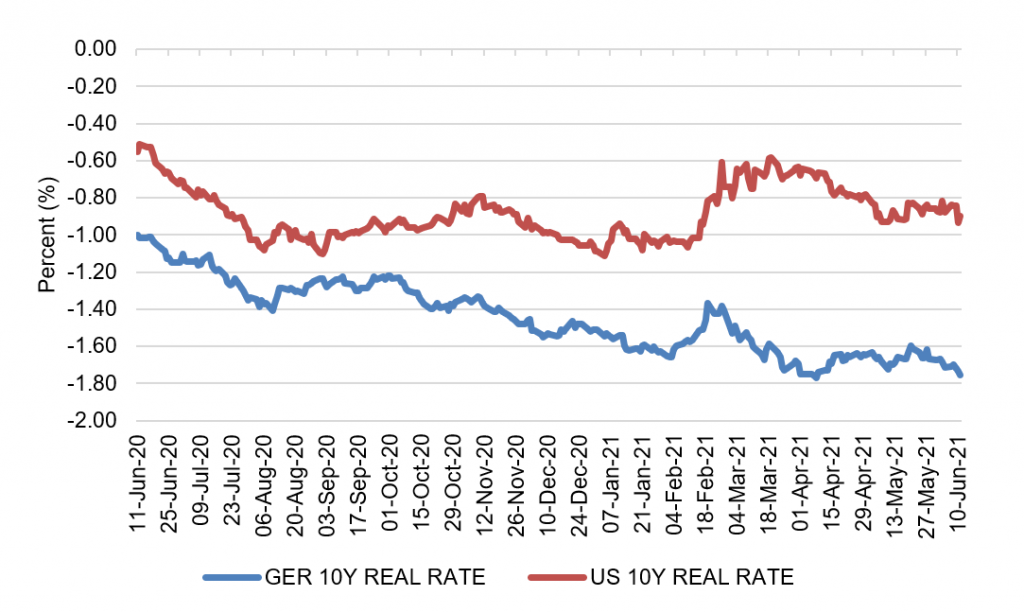

The US is not alone in pricing in rising inflation and a falling real cost of money. German 10-year debt, for example, has more than doubled its implied inflation rate over the last year, and, since September, added inflation expectations in rough parallel with the US (Exhibit 1). German debt also reflects a steadily lower real rate (Exhibit 2). Through February, German 10-year real rates tracked US 10-year real rates but have fallen substantially more since, the recent decoupling arguably reflecting a faster US rebound from Covid with less of a liquidity overhang.

Exhibit 1: Both US and German 10-year debt reflect rising inflation expectations

Source: Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

Exhibit 2: Both US and German 10-year debt reflect falling real rates

Source: Bloomberg, Amherst Pierpont Securities

Rates are likely to rise not from steadily pricing in higher inflation but from steadily pricing in a higher real rate. That should start around the same time the Fed starts to take cash out of the system. And that happens not during tapering or its immediate aftermath but when the Fed starts to raise rates and ultimately starts to draw down its QE portfolio and renormalize its balance sheet. Fed funds futures and OIS price in a substantial chance of Fed hikes only starting in 2023, so that should mark the beginning of a slow march to higher real and nominal rates.

* * *

The view in rates

The money markets remain the poster child for excess liquidity. Even though bank liabilities ran roughly flat through May, government money market mutual fund balances rose $119 billion. Overnight Treasury repo and SOFR sit around 1 bp. Recent settings on 3-month LIBOR have dipped to another record at 11.9 bp. Fed reverse repo agreements, offering a 0% rate, stood June 11 at $548 billion.

Concerns about a persistent oversupply of cash also have shaped the longer end of the curve. The 10-year note has finished the most recent session at 1.45%, down 10 bp on the week, despite 10-year breakeven inflation at 2.35%, down 7 bp on the week. The negative 90 bp 10-year real rate implies heavy supply of 10-year cash against limited demand to borrow.

The Treasury yield curve has finished its most recent session with 2s10s at 131 bp, 10 bp flatter from just a week ago. The 5s30s curve has finished at 140 bp, flatter by 5 bp from a week ago.

The view in spreads

MBS spreads have widened notably in recent weeks. The nominal spread between par 30-year MBS and the interpolated 7.5-year Treasury yield closed recently at 70 bp, wider by 8 bp from local tight levels. Refi risk may also be creeping back into MBS. Primary 30-year mortgage rates have dropped below 3.0% in several surveys, and data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show employment in the mortgage industry up 30% from three years ago, giving originators plenty of capacity to chase loans.

In credit, low rates should continue supporting corporate balance sheet strength. Ratios of EBITDA to interest expense are in the middle of the range despite high ratios of debt to EBITDA. Investor demand for yield should keep spreads relatively tight.

The view in credit

Consumers finished the first quarter of 2021 with net worth up $5 trillion. Aggregate savings jumped again as did home values and investment portfolios. Consumers have not added much debt. Corporate balance sheets have taken on more leverage, although mitigated by strong cash balances and low interest costs. EBITDA-to-interest-expense is at healthy levels. Strong economic growth in 2021 and 2022 should lift most EBITDA and continue easing credit concerns. Eventually, rising interest expense in 2023 should compete with EBITDA growth.