The Big Idea

Managing the yield curve

Stephen Stanley | January 22, 2021

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

The Fed might look like it has done Treasury and the federal government a great favor by purchasing massive amounts of Treasury securities and helping finance the rise in the budget deficit required by the pandemic. But on closer examination, the Treasury’s borrowing and the Fed’s buying have been like the proverbial ships passing in the night. The Treasury has focused its borrowing in the bill sector while the Fed stopped buying bills after the pandemic began and bought an unprecedented amount of coupon securities across the yield curve. Treasury bill supply consequently exploded in 2020 while the outstanding float of Treasury coupon securities excluding Fed holdings actually dropped substantially.

Treasury debt issuance

The pandemic created urgent federal borrowing needs not seen since World War II. Not only did the budget deficit increase, but the government shoveled massive amounts of money out the door, with rebate checks and unemployment benefits authorized in the CARES Act quickly distributed beginning in April. The federal government also shelled out billions for health care, testing and vaccine research as well as funds forother relief programs like PPP. And Treasury delayed the April 15 deadline for individual and corporate income taxes to July 15.

The federal budget deficit went from running at an already-hefty $1 trillion annual pace before the pandemic to an eye-popping $2 trillion in the second quarter of 2020 alone. Coupled with Treasury debt managers’ desire to beef up the cash balance to cover the possibility of a further unexpected bulge in expenses, federal borrowing in the spring of 2020 topped $2.7 trillion.

Due in part to its longstanding policy of fostering regular and predictable issuance as well as the realities of the market, Treasury debt managers were not in a position to raise massive amounts of new money from its coupon offerings in a matter of weeks. Out of necessity, they turned to the bill sector. In particular, debt managers issued close to $2 trillion in cash management bills in a matter of a few months.

At that time, Treasury debt managers also began raising the monthly coupon auction sizes by unprecedently large increments. These hikes are an effort over time to “term out” the issuance, but it takes a while for the monthly increases to compound and add up to a meaningful amount in the context of $3 trillion annual budget deficits.

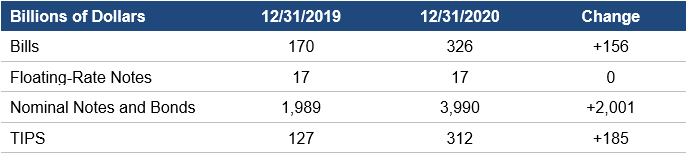

Both Treasury bill and coupon issuance rose sharply through 2020, but bills accounted for a larger proportion of the increase and rose by much more in percentage terms (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Outstanding Treasury debt held by the public, including Fed holdings

Source: Treasury Dept.

Federal Reserve Holdings

Prior to the pandemic, the Federal Reserve had two programs going simultaneously to buy Treasury securities. First, the Fed was rolling over its MBS runoff into Treasuries, which required a modest amount of purchases each month, spread evenly across the yield curve from bills all the way to bonds. Second, after seeing the shrinkage in its balance sheet through the summer of 2019 create a scarcity of reserves and dislocations in the repo market, the Fed began to buy T-bills to increase the level of reserves in the financial system. Pre-pandemic, the Fed was actually increasing its bill holdings by more than it was building its coupon position.

When the pandemic led to severe financial market upheaval, two key developments in March altered the Fed’s approach. First, the Fed stopped buying bills because of a flight to quality and liquidity, which lead to an immense increase in the market demand for bills. The Fed did not want to create or exacerbate a shortage of bills. Second, a sharp reduction in liquidity for off-the-run Treasuries created wild swings in coupon prices, and the Fed responded by becoming the buyer of last resort, embarking on a massive buying campaign of off-the-run Treasury coupons split evenly across the yield curve according to the outstanding debt in each sector.

As financial markets returned to normal, the Fed gradually reduced the pace of its coupon purchases but continued to buy at a substantial pace, eventually shifting the stated rationale of the program away from market functioning and toward monetary policy accommodation. By year-end, the Fed was buying $80 billion in Treasury coupons a month and was still maintaining steady bill holdings.

The Fed through 2020 bought roughly $2 trillion in nominal coupons and a substantial amount of TIPS but barely increased bills holdings for the year, and not at all after March (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Fed SOMA Treasury debt holdings

Source: Treasury Dept.

Net supply: combining the two

Combining Treasury issuance and Fed holdings, the 2020 increase in outstanding supply of Treasury bills was massive. Even accounting for the Fed’s SOMA account, outstanding supply more than doubled, rising by nearly $2.5 trillion, and the Fed only absorbed a small portion of that.

In contrast, net of the Fed, outstanding Treasury coupon supply actually declined in 2020 by almost $400 billion, while outstanding TIPS float sank by over $100 billion, or almost 10%.

Whether it was intended or not, the impact of the separate decisions by Treasury and the Fed have created massive swings in the relative supply of short paper versus longer-term paper and presumably has had an impact on the shape of the yield curve.

Although radical changes in the behavior of either the Treasury or the Fed look unlikely in the near term, once the pandemic is over, presumably Treasury borrowing needs will diminish, which will lead to an unwinding in a good portion of the spike in bill issuance, while the FOMC will eventually begin to taper the pace of its coupon purchases, unwinding in both cases the trends established in 2020, though the pace on the way out will likely be far more gradual than the abrupt changes seen in the spring of 2020.