Uncategorized

Picking pools to avoid Ginnie Mae buyouts

admin | September 11, 2020

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors.

The prospect of fast prepayments from buyouts of delinquent loans is complicating decisions to invest in Ginnie Mae MBS, and the spread between Ginnie Mae and conventional MBS has collapsed. Some large banks have aggressively bought out loans, driving up prepayment speeds in June and July. Most other servicers have large delinquent pipelines that investors fear could be bought out at any time. This complicates the investment decision because some servicers have more than 10% of their loans eligible for buyout. One way to avoid this risk is to focus on servicers with low current delinquency rates, low buyouts or both. That puts an investor in pools with less risk than the market has priced.

Ginnie Mae servicers are permitted to buyout loans at par as soon as they become 90 days delinquent. Before July, Ginnie Mae allowed loans that cured to be re-pooled immediately. Servicers anticipated the opportunity of buying out loans at par and re-pooling at a significant premium. Prior estimates, discussed in this article, suggest that banks could have earned 339% annualized return on buyouts, and non-banks earned 296% returns.

To protect investors from fast prepayments Ginnie Mae instituted pooling restrictions in July that sharply reduced the economics of re-pooling these loans. The new rules required servicers to hold loans on balance sheets for at least six months before re-pooling and prohibited delivering these loans into TBA-eligible pools. These changes lowered annualized returns to an estimated 61% for banks and 18% for non-banks.

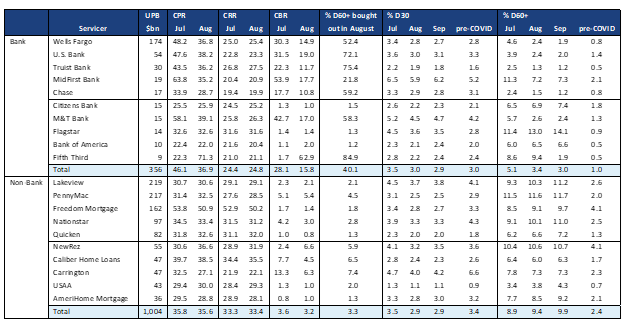

Banks continued to buyout delinquent loans in July and August (Exhibit 1). However, the high buyout banks like Wells Fargo and Chase have very few delinquent loans left to buyout so the overall effect on prepayment speeds is shrinking. But a few other banks, and almost every large non-bank servicer, has a very large portion of their loans eligible for buyout.

Exhibit 1: Non-bank delinquencies are building

CRR: Conditional Repayment Rate (housing turnover and refinancing). CBR: Conditional Buyout Rate. Source: Ginnie Mae, eMBS, Amherst Pierpont Securities

Although non-bank buyouts have been low, there is no guarantee this will remain the same. One possibility is a bank could acquire MSR from a non-bank and finance the buyout themselves, sharing in the profits. Also, the FHA just announced that some borrowers can be refinanced as soon as forbearance ends. Servicers will be in contact with borrowers when they call for forbearance extensions or exit forbearance, and servicers might find it worthwhile to offer a payment deferral to cure the delinquency and then a refinance. The refinance would benefit the borrower with a lower payment and the servicer can still make good money on the refinance.

The best way to avoid this risk is to look for Ginnie Mae servicers that have not bought out many loans but also have low delinquency rates. One servicer that stands out is USAA. Their 60+ day delinquency rate is very low compared to other non-bank servicers although they haven’t bought out many loans. Rather, their delinquency rate is low because they have had fewer loans become delinquent throughout this crisis. This suggests USAA pools could perform much better than other servicers’ pools if there is a second wave of Covid-19 that triggers new delinquencies.

One concern with USAA is that they service only VA loans, which typically exhibit very negative convexity. However, USAA loans tend to prepay more slowly than other VA lenders’ loans. The Amherst Pierpont servicer prepayment ranking shows that USAA loans typically prepay almost 50% below comparable VA loans from other lenders. Another concern is that most VA delinquent loans are likely to require loan modifications, which mandates a buyout, whereas FHA loans might cure and remain in the pool if servicers are unable to finance the buyouts.

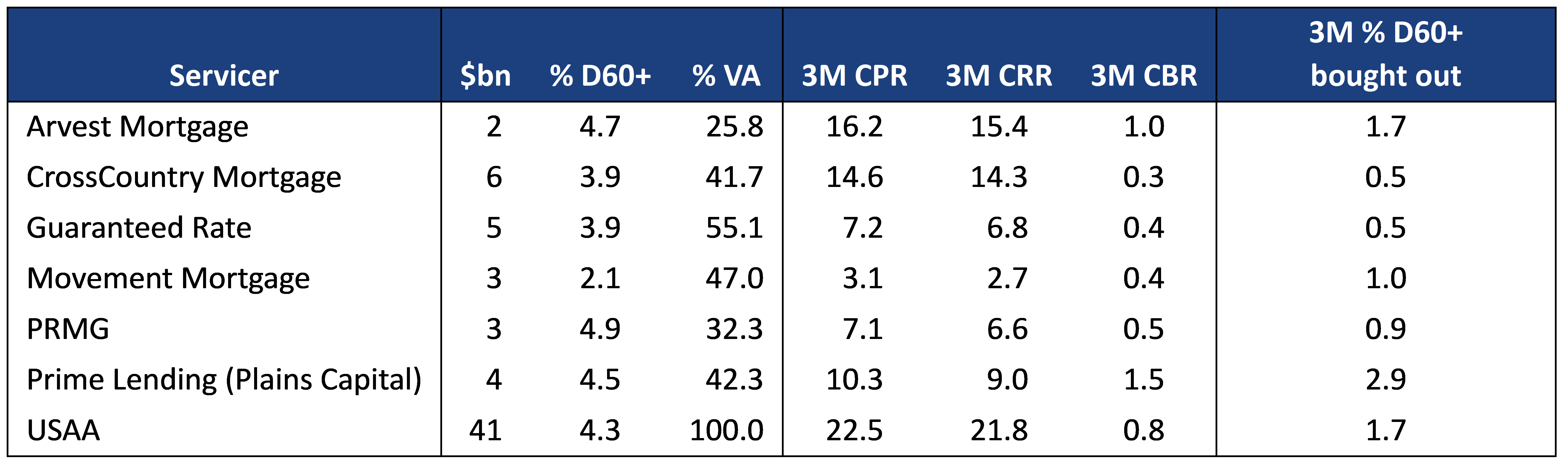

There are a few other, smaller, non-bank servicers that have not been buying out delinquent loans, yet have low delinquency rates (Exhibit 2). For example, CrossCountry Mortgage has only 3.9% of their loans at least 60 days delinquent and buyout rates have averaged only 0.3 CPR over the past 3 months. Their pools should have far less buyout risk than the multi pools.

Exhibit 2: A few servicers have low delinquency and buyout rates

Prepayment speeds and %60+ bough out averaged over June, July, and August. CRR: Conditional Repayment Rate (housing turnover and refinancing). CBR: Conditional Buyout Rate. Source: Ginnie Mae, eMBS, Amherst Pierpont Securities

Another way to avoid buyouts is to buy pools backed by the banks that have conducted heavy buyouts and have very few delinquent loans remaining. For example, Wells Fargo pools have only 1.9% of their loans at least 60 days delinquent. However, these pools are exposed to the risk of a second wave since any new delinquencies are likely to be rapidly bought out.

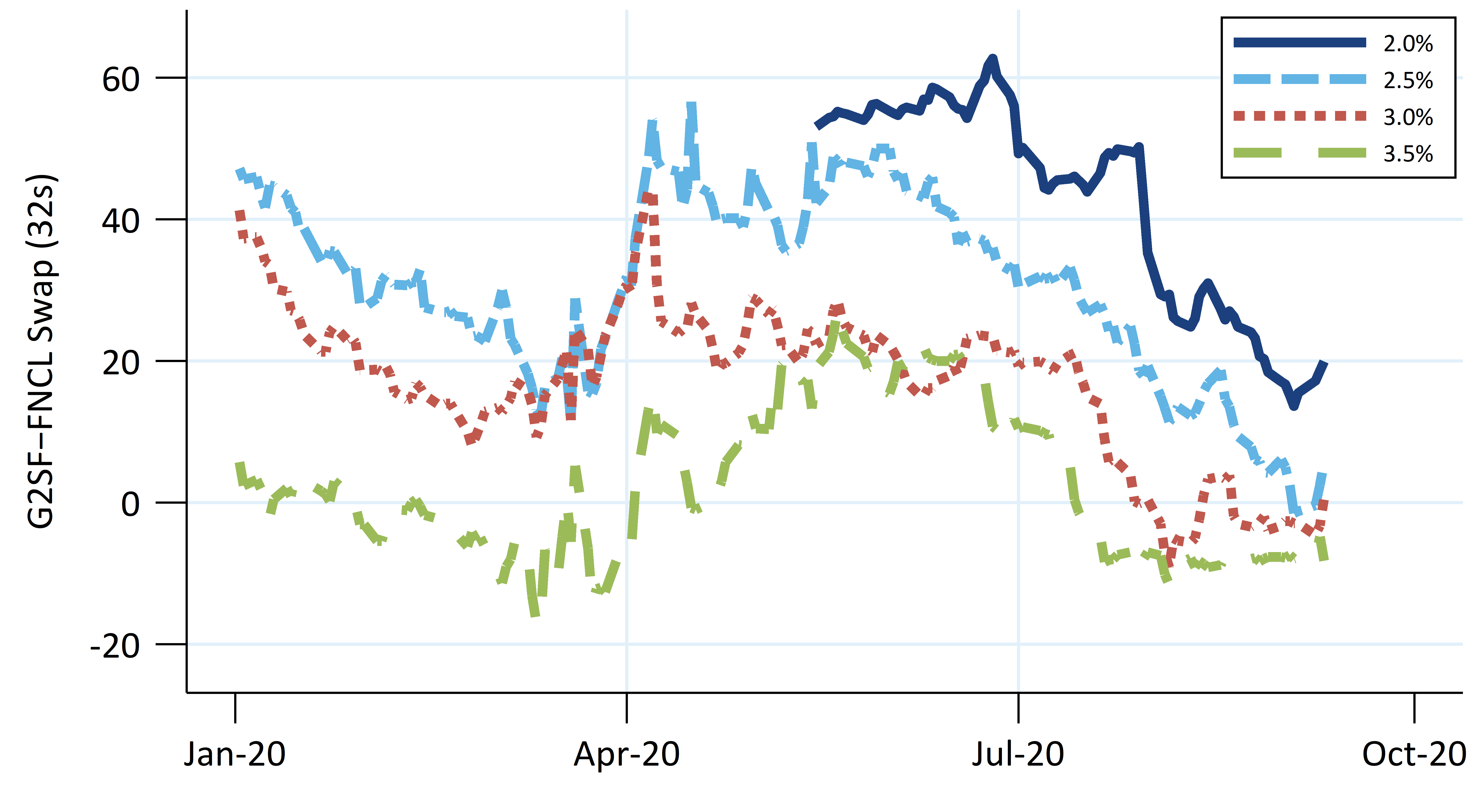

Prices for Ginnie Mae MBS suggest that the buyout risk is already priced in. The Ginnie–Fannie MBS swap has fallen sharply since the beginning of June as investors became worried about the risk of buyouts (Exhibit 3). The 2.5% and 3.0% swaps are currently at the lows for the year. The 3.0% and 3.5% swaps have been trading relatively flat for most of August, suggesting buyout risk has been priced in. By selecting a servicer with low delinquencies, a low tendency to buyout delinquent loans or both, investors can own Ginnie Mae pools inexpensively relative to conventional pools without taking the full risk currently priced into the swap.

Exhibit 3: The Ginnie–Fannie swap has plummeted throughout the summer

Source: Yield Book, Amherst Pierpont Securities