Uncategorized

Execution on Main Street

admin | April 17, 2020

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

The Fed has pulled big parts of its 2008 crisis playbook off the shelf to address problems brought on by coronavirus, largely with good and predictable effect so far. But the Fed has also headed into new and more challenging territory. The $600 billion Main Street lending programs target corporate balance sheets that have relied on low rates and rising leverage ever since the last crisis. The execution risk there looks daunting, which could weigh on the economy and markets.

The Fed foray into leveraged lending

The Main Street programs try to address a part of the economy that has become much more important since the last crisis. The Main Street New Loan Facility targets smaller companies that need new bank loans of up to $25 million while the Main Street Expanded Loan Facility targets borrowers with existing bank loans that need up to $150 million. Combining existing loans, undrawn lines of credit and debt supported by the Fed’s Main Street facilities, new borrowers can have a ratio of total debt to EBITDA of 4x while existing borrowers can take leverage up to 6x.

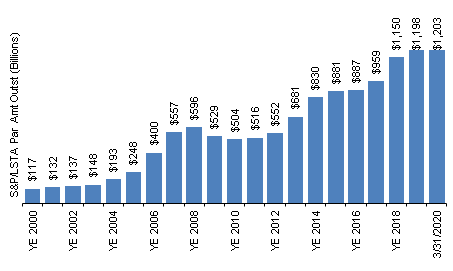

This type of leveraged lending has supported a steadily rising share of GDP. Leveraged lending between 2008 and today has run from nearly $600 billion to more than $1.2 trillion, with its equivalent share of GDP rising from 4% to 5.5% (Exhibit 1). Leveraged loans currently help fund more than 1,500 businesses across a wide range of industries including many affected by coronavirus—hotels and casinos, retailers, and oil and gas operators, among others.

Exhibit 1: Leveraged lending has doubled since the 2008 crisis

Source: S&P

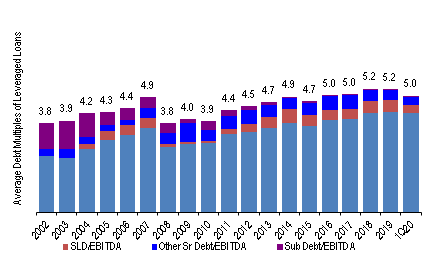

This market is clearly in the Fed’s sights since ratios of debt to gross earnings for leveraged borrowers have run around 5x in recent years (Exhibit 2). With the Fed’s limit of 6x on the facility for existing borrowers, something in the neighborhood of a half or more of leveraged borrowers would quality based on leverage. And based on leverage, these businesses have limited ability to absorb the sharp downdraft in earnings that started in March and looks likely to run through 2020 for many and, for some, far beyond. That may be why S&P has downgraded leveraged borrowers at a record pace in the last three months, with most coming in March.

Exhibit 2: Leverage for new loans has run around 5x in recent years

Source: S&P

Although the Fed still needs to announce a slew of details, it is already clear that the path from concept to execution for Main Street is strung with a web of trip wires. Among other complications, the Fed may struggle to manage the risk in lending to these borrowers, current lenders may not want the borrowers to take on more debt and the borrowers themselves may not want the constraints that come with a Fed loan.

The Fed’s challenge in managing the risk

The biggest challenge may come in the Fed’s ability to manage the lending risk. The Fed traditionally lends either to regulated depositories, foreign central banks, buys Treasury or agency debt and MBS or lends against investment grade debt. Most leveraged lenders are rated ‘BB’ or lower. The Main Street programs require the bank making the loan to retain 5% participation, effectively borrowing the bank’s underwriting expertise for the Fed program. Since 2010, however, banks have made up less than 10% of primary market investors in leveraged loans, and bank expertise and appetite might be limited. The Fed also may not be comfortable as just another lender. It may want to come in as senior to all other lenders, which creates a separate set of obstacles. The Fed will need to have a view on a wide set of financial covenants in play in a leveraged loan, and those covenants will have to be acceptable to a wide enough set of borrowers for the money to flow quickly into the distressed sector.

The challenge from current lenders

Current lenders may also have a view on whether a borrower should take a Main Street loan, and that view may be legally enforceable. Even though covenants in leverage loans have loosened for years, more than two thirds of loans made in 2019 still included limits on the ratio of debt to EBITDA. Existing lenders may decide it is far more important to protect their ability to recover principal in bankruptcy than it is to get an uncertain lifeline from the Fed.

The challenge for borrowers

Finally, borrowers will have to decide if they want to accept the public policy conditions that come with Main Street. Among others detailed by the Fed so far, they include:

- The borrower will not use the loan to repay or refinance existing debt

- The borrower will not cancel or reduce existing lines of credit

- The financing is required due to ‘exigent circumstances’ from COVID-19

- The borrower will make ‘reasonable efforts’ to maintain payroll and retain employees during the loan term

- The borrower meets EBITDA leverage requirements

- The borrower will meet compensation, stock repurchase and capital redistribution requirements of the CARES Act

- The borrower meets CARES Act conflict of interest rules

In principle, the Main Street programs could become one of the post powerful weapons in the Fed’s arsenal against the effects of coronavirus. The $600 billion tagged for the programs so far could go a long way to supporting leveraged borrowers through tough times. In practice, however, the obstacles to getting the cash into borrowers’ hands look daunting. The programs also stop taking new loan participations on September 30. There’s a lot of work to do between now and then, and none of it looks easy.

Failure of a significant set of leveraged lenders could drag an important share of GDP into restructuring or bankruptcy, tying up productive capacity for months or years. The effect on productivity, growth, inflation and rates could last longer than the effects of coronavirus itself.

* * *

The view in rates

The current 0.64% rate on 10-year Treasury debt implies an average real rate of -38 bp and inflation of 102 bp. Futures now imply policy rates at zero-bound into the middle of 2022. Fed QE should continue to signal the Fed’s intent to keep rates low for long. But QE along with other monetary and fiscal interventions of historic magnitude should keep concerns about inflation on the market agenda and keep the yield curve steepening.

The view in spreads

Spreads markets with Fed or fiscal support should continue tightening, and the impact of scarcity, broad liquidity, falling default and prepayment premia should tighten other debt sectors, too. Those markets now include Treasury and agency MBS, agency CMBS and investment grade corporate debt, a wide range of ABS, legacy CMBS and ‘AAA’ static CLOs.

The view in credit

The immediate risk in credit is from companies with high fixed costs and a sharp drop in revenue from current efforts to avoid coronavirus infection. Rating agencies have started downgrading companies and related structured products, CLOs in particular, at a record pace. Companies with the highest leverage are first in line. Until the arrival of pandemic, the consumer balance sheet has been extremely strong. The coming sharp rise in unemployment should change that, although the CARES Act could substantially cushion the blow. Nevertheless, delinquencies and defaults on mortgage and consumer loans have already started to climb quickly.