Uncategorized

Regulators tune the Volcker rule

admin | January 31, 2020

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

Small changes can make a big difference when it comes to the way banks manage their current $13.8 trillion in assets. And regulators in the last few days have recommended some small changes in the Volcker rule governing bank investment in debt and credit funds. The market in CLOs and leveraged credit seems the clearest potential beneficiary, although other corners of the capital markets could see new bank interest, too.

Constraints on CLOs

Even though banks currently hold around $90 billion in CLOs mainly in ‘AAA’ classes, regulations have sometimes clouded banks’ ability to invest. The Volcker rule intended to eliminate bank investment in funds that could put insured deposits at risk but excluded loan securitizations from that list of funds. The rule has led CLOs to hold only leveraged loans and exclude high yield debt. It has also ruled out CLO participation in debt restructurings that might exchange loans for equity or related instruments—limiting CLOs ability to manage distressed credits.

Volcker also stops banks from holding ownership interests in funds, which some regulators interpret broadly to include debt interests with the right fire a manager for cause. Most ‘AAA’ CLOs have this right, although banks have differed in their willingness risk an interpretation that ‘AAA’ CLOs violate Volcker.

Litigation has also challenged bank holdings of CLOs. A suit pending against JP Morgan, Kirschner v. JP Morgan et al., argues that the term loans usually held by CLOs fall under federal securities laws and do not qualify for the Volcker allowance for loan securitizations. If that suit were decided against JP Morgan, banks potentially would need to sell their current CLO holdings.

Addressed by the latest proposed changes

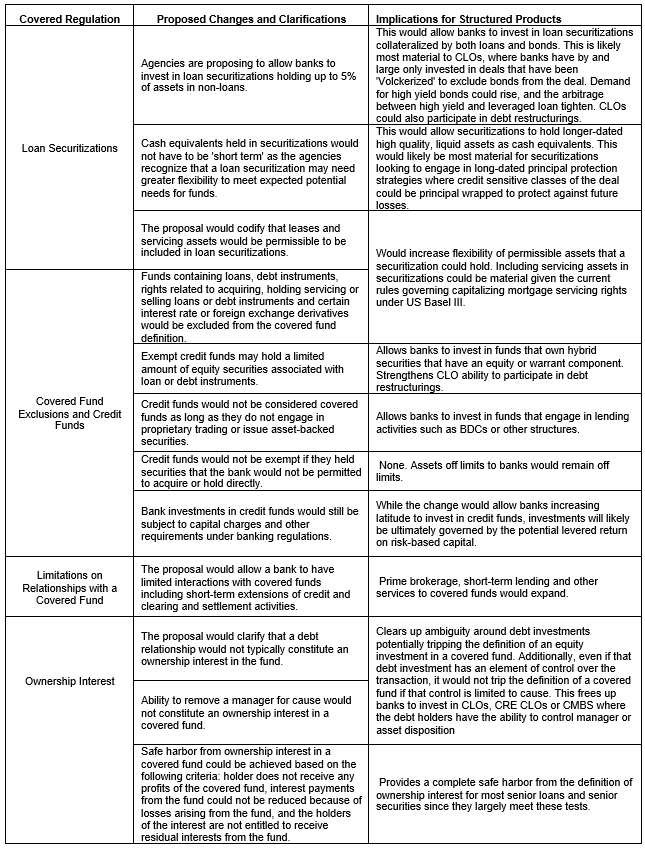

Some of the key provisions of the Fed’s latest proposal address constraints around CLOs as well as potentially expanding bank investment in other types of debt funds, business development companies and the like (Exhibit 1). The proposed changes would allow banks to invest in funds with up to 5% of assets in non-loan instruments, opening the door to holdings of high yield debt, equity, warrants and other instruments. The proposal also specifies that funds could hold a limited amount of equity associated with loans or debt, which seems targeted to allowing funds to participate in debt restructurings. The proposal specifies that the ability of a debt holder to fire a manager for cause would not constitute an ownership interest. And the proposal creates a safe harbor from litigation like Kirschner v. JP Morgan, laying out criteria that most CLO loans and high yield debt would be able to meet.

Other areas, too

Banks could become more invested in business development companies under the proposed changes, getting more exposure to the middle market loans usually owned by those investors. And banks could invest in securitizations that included mortgage servicing and leases.

Most of these changes seem reasonable clarifications of grey areas in the Volcker rule. Banks sidelined by earlier uncertainty around the rule seem likely to take a new look at a range of assets, especially CLOs and especially in a market where yield is increasingly hard to find.

Exhibit 1: A summary of key Fed proposed modifications to the Volcker rule

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Amherst Pierpont Securities

***

The view in rates

The sharp drop in rates over the last two weeks seems equal parts fact and fear, and fear seems to be winning. The fact part highlights the growth in China’s share of global GDP since the SARS outbreak in 2003: around 4% then, around 19% now. So it is true that the current quarantines in China, the restrictions on travel and the like have almost certainly hurt China’s GDP. Of course, it is likely that pent up demand would resurface once there’s clarity on the coronavirus and GDP would partially or fully catch up. The fear part revolves around scenarios that hint of pandemic. At this point, the coronavirus seems roughly as contagious as SARS but much less fatal, and estimated time to a tested and approved vaccine ranges from a year or more. Given the emerging scientific and public health collaboration to address the outbreak, it seems likely that the uncertainty around the outbreak will fall quickly. As it falls, rates should rise.

The view in spreads

The appetite for spread and compounding income is still strong, but investors have clearly stepped back to watch the coronavirus play out. It seems reasonable. After all, it’s a risk that’s undoubtedly hard to price. Still, the US economy looks healthy enough to keep credit concerns at bay for investment grade companies and even most high yield companies, so spreads have room to compress further once uncertainty around the virus drops. MBS has some room to run tighter even though low rates stand to keep prepayments elevated through the spring, especially in Ginnie Mae MBS. If the economy moves above current expectations of less than 2% real GDP growth, spreads should tighten further.

The view in credit

A variety of measures of corporate leverage remain high, but leverage spells trouble only if growth falls below current expectations and financing for leveraged borrowers tightens. That does not look likely. It looks more likely growth might slightly exceed expectations, lifting corporate fundaments. As for the consumer, that is a story of generally continued strength with low unemployment, strong income, rising net worth and low debt service as a share of income.