Uncategorized

The possible highs and lows of 2020 prepayments

admin | December 13, 2019

This document is intended for institutional investors and is not subject to all of the independence and disclosure standards applicable to debt research reports prepared for retail investors. This material does not constitute research.

The MBS market will begin 2020 with roughly 35% of loans having at least 75 bp of refinancing incentive, so investors still have substantial prepayment risk to manage. The safe harbor of specified pools may prove a little less valuable than it did this year as the quality of TBA improves in the year ahead. One thing that should persist is the speed gap between Ginnie Mae and conventional loans, especially as the Ginnie Mae loans season into their prime refinancing window. And speeds driven by housing turnover should remain strong.

Specified pool pay-ups could fall later in the year

Specified pool pay-ups should soften as the quality of the TBA contract improves. In 2019, TBA was dominated by pools with extremely high gross WACs produced from late 2018 until the June launch of UMBS. With the launch of UMBS, the Federal Housing Finance Agency and along with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac took steps to cap the amount of servicing that can be retained and cap the overall spread between gross WAC and pool coupon. Since then, spreads have tightened, although not all the way back to historical averages. The WAC dispersion across pools has also improved.

Over time convexity should improve on the high WAC pools, which could cause specified pool pay-ups to fall in the latter half of 2020. Pool WACs will likely drift lower due to prepayments, the remaining loans should be less likely to refinance due to burn out, and even the least seasoned pools will season past 12 months. These pools may even cease to be worst-to-deliver. As TBA quality improves and the TBA price increases, specified pool pay-ups should drop.

The biggest caveat to improvement in TBA is the recent jump in the regular conventional conforming loan limit from $484,350 to $510,400, and the move in the large loan limit from $726,525 to $765,600. Servicers have more room next year to securitize larger loans and consequently erode the convexity of TBA. On balance, limits on WAC should outweigh the impact of larger average loan balances.

The gap between Ginnie Mae and conventional speeds persists

Ginnie Mae prepayment speeds should remain strong relative to conventional speeds for the first half of 2020. Both FHA and VA programs offer their borrowers easy streamline refi programs. The VA borrower especially tends to be a better credit and more similar to the conventional borrower than an FHA borrower. This means the VA borrower is more capable of refinancing and explains why VA loans have such a steep S-curve.

Both the FHA and VA have strict seasoning requirements for using the streamlined refinance programs—an FHA loans needs to have 6 months seasoning and a VA loan needs effectively 7 months seasoning. All of FHA and VA loans that were originated in early 2019 at higher rates are starting to season past those thresholds and prepay very quickly due to pent-up demand.

One change in 2020 is worth monitoring for its potential to cause new multi pools to prepay faster and hurt the Ginnie TBA. Over the summer, Congress removed VA loan limits effective in 2020. If Ginnie Mae allows VA loans into the multi pools regardless of loan balance then those multi pools will have worse convexity and lower the value of the Ginnie TBA. However, neither the VA or Ginnie Mae has yet announced how they will handle the removal of limits. For example, Ginnie Mae could require VA loans to meet the FHA high balance limits in order to be pooled in the multi pools, and higher balance loans would have to go into customs. That seems the likely outcome. But if nothing is done then pay-ups should increase for custom pools that contain no VA loans.

Turnover speeds should remain strong

Purchase production has increased for the last few years, and 2020 should meet or slightly exceed the totals from 2019. Besides pushing net supply to around $300 billion this suggests that turnover-driven prepayments will remain strong. That’s because most new purchase loans sold to the GSEs were for properties that had previously been mortgaged, and those mortgages were predominantly securitized with the GSEs.

Broader prepayment risk

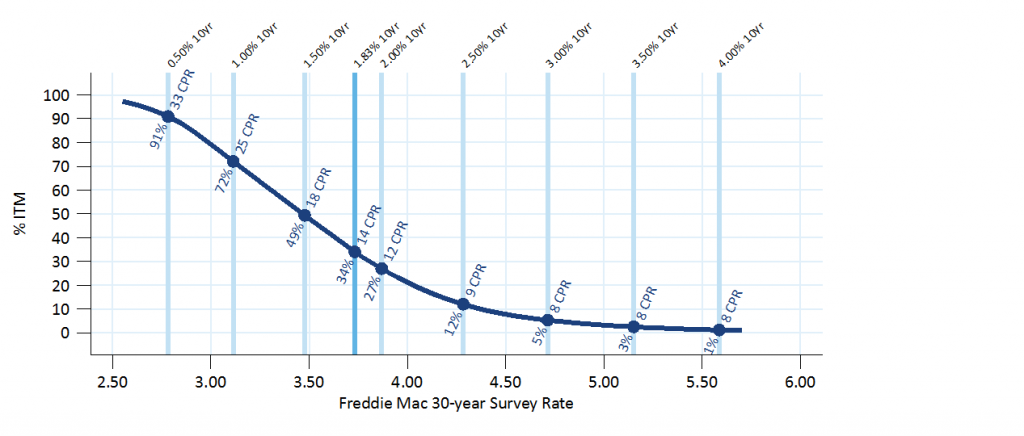

Most of the 30-year MBS market remains concentrated in 30-year 3.0%s and 3.5%s, which, at current interest rates, are very negatively convex. And many of those pools are between six month and 24 months seasoned, which is the prime window to refinance. MBS speeds could accelerate quickly if rates were to decline and could slow quickly if rates were to rise. A 50 bp drop in rates could push overall speeds faster by 7 CPR and a similar rise in rates could slow overall speeds by 4 CPR (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: 34% of MBS are in-the-money at current rates

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, eMBS, Amherst Pierpont Securities

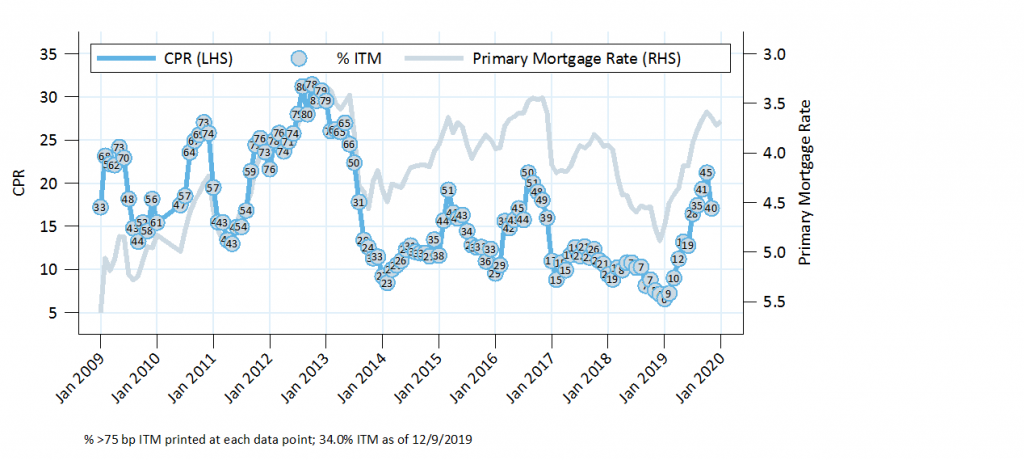

Prepayment speeds have been running a bit faster than historical for the same level of refinanceability, but this difference should drop over the course of 2020. Exhibit 2 shows the historical relationship between prepayment speeds and the share of loans that are at least 75 bp in-the-money. If rates were to remain unchanged then aggregate prepayment speeds over a year should average roughly 14 CPR—faster in the summer and slower in the winter. Current speeds have been faster due to the large number of low WALA, low SATO loans that are deep in-the-money. Burnout and seasoning should pull aggregate speeds back to average levels.

Exhibit 2: Historical CPR and % in-the-money over time

Source: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, eMBS, Amherst Pierpont Securities

The potential for rates to generally come in below forwards and for volatility to episodically rise should create relative value opportunity in taking prepayment risk. Trimming exposure to some of the richer specified pools sectors, underweighting more negatively convex Ginnie Mae pools and taking some extension risk in light of strong turnover could add to MBS portfolio performance.